July 12, 2018

I Have the Right To

Sacred Heart alum and St. Paul’s School sexual assault survivor brings her story home

By Andrew Deck

Chessy Prout took the stage at the International School of the Sacred Heart (ISSH). Addressing a packed audience of students, parents, former teachers and family friends, she sat in front of a projected collage of childhood photos, collected memories of an upbringing in the Tokyo international community. “Right now my mind is spinning just being here and being overwhelmed with being here,” she said at one point during her talk at the Hiroo campus in May. “This is my beginning here and I’m just wondering,” her voice breaking, “how that little girl…[would] never think that this would be my life now coming back. I’m just so grateful to be here and be able to see the people that gave me the strength to know how to speak up.” The homecoming marked the first time Prout had addressed the community at her childhood school since an assault at the age of 15 dramatically altered the course of her life. Reflecting on the time that’s past since, she shared, “I’ve gone from a place of fear and anger, to a place of strength and anger.”

In the spring of 2014, Prout was finishing her first year of high school at the prestigious St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire when a senior boy sexual assaulted her on campus. A criminal trial revealed that the perpetrator had targeted her months earlier as part of an archaic school tradition called the “Senior Salute,” in which graduating boys competed to hookup with, or “slay,” as many freshmen girls as possible. The case exposed entrenched misogyny in the boarding school and affirmed the community’s unwillingness to confront its toxic campus culture. American media outlets grabbed ahold of the case at the wealthy private school, turning one of Prout’s most personal and painful experiences into a national headline.

While Chessy Prout remained anonymous throughout the trial, the perpetrator received extensive airtime. Most articles at the height of the 2015 media fervor noted Owen Labrie’s soccer-captain status, his school service award and his revoked full-ride admission to Harvard, implicitly sympathizing with the dashed futures of the young man. Word counts were limited when it came to a full consideration of the costs facing the teenage survivor or the burdens placed on her family. Prout’s father was fired from his job after taking a leave to deal with the criminal justice process, his boss remarking, “I certainly hope your daughter gains better judgment in the future.”

“The perpetrator was given these shining accolades; I was the nameless, faceless victim,” Prout told Metropolis during her recent visit to Tokyo. “Someone could write adjectives — naive, flummoxed, preppy — but no one cared about who I was or what I was going through. No one knew what my PTSD looked like. No one knew what my weekly panic attacks looked like.” In nightly news clippings of her testimony, Prout spoke from out of frame, her voice distorted beyond recognition, as cable news cameras focused their lenses on Labrie’s face. It wasn’t until a “Today” show interview in the fall of 2016 that Prout came forward publicly, putting a name and a voice behind the label of St. Paul’s survivor.

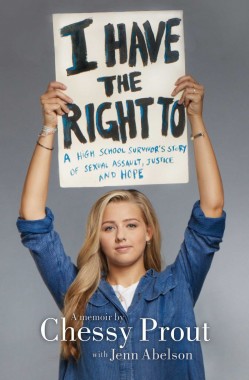

I Have the Right To: A High School Survivor’s Story of Sexual Assault, Justice, and Hope, the book Prout’s co-written with Boston Globe Spotlight Team reporter Jenn Abelson, is the next step in this shift from anonymous survivor to public advocate. The book frankly documents Prout’s time at St. Paul’s and during the trial, supplementing a firsthand account with text messages and email exchanges. The now 19-year-old hopes the book will take attention away from the perpetrator and refocus the narrative on her perspective and her advocacy. “Through writing this book, I wanted to put the humanity behind the word victim or survivor.”

Prout’s childhood in Tokyo has often been bracketed in public events since the “Today” interview. Raised in Hiroo, she attended ISSH with her sisters until the age of 11, before the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake prompted the family to relocate to a home in Naples, Florida. Prout’s heritage — her father is half-Japanese — and international upbringing never fit neatly into the pre-packaged mold of a New England prep school girl. “I’ve kind of accepted that places and people will not know who I am 100 percent, even after the book’s been published,” explains Prout, who at a young age has already weathered years of critical media coverage and threatening online hate sites. “As much as I put myself into it, it’s not all of me at the same time, there’s still so much more to who I am.”

Having spent more than half of her life in Japan, she credits lessons from the Sacred Heart community and Japanese culture with getting her through these past few years. “My older sister looks much more Japanese than I do, so does my little sister,” says Prout, who sports long blonde hair and blue eyes. “But my parents always joke that I acted the most Japanese growing up. It really helped form my identity and I’m proud of that.”

The plan was always to bring the I Have the Right To book tour back to Tokyo, according to Abelson. Part of this return was confronting the uncomfortable resonance the story has in the international school community. Last summer, Sacred Heart’s headmistress announced an investigation into sexual abuse allegations against a former teacher who had worked at the girls school from the 1990s until the mid-2000s. “I wondered about the survivor and how the family are doing. I wondered what we can do to help. I wondered what we could do to bring that conversation to the Tokyo community and especially the expat community here,” explains Prout of her reaction to the news. The announcement followed public exposure of long term sexual abuse at two other Tokyo international schools. In 2014, the all-boys St. Mary’s International School announced sexual abuse that had spanned decades and implicated a religious brother who at one point served as the elementary school principal. That same year, The American School in Japan admitted a history of sexual abuse by celebrated teacher Jack Moyer. At least 19 girls were found to be confirmed survivors from his time at ASIJ in the ’70s and ’80s, although he was affiliated with the school until 2000. Administrators at both schools were found to have received reports of the sexual abuse from survivors over the years but had not taken substantial disciplinary or criminal action. This past May, Nishimachi International School publicly confirmed its own historic abuse by former teacher Jim Hawkins after pressure from survivors and alumni. They have retained a law firm to further investigate allegations.

Prout’s narrative in I Have the Right To is, in part, about institutional failings in sexual assault cases. It’s about the inability of an elite private school to ensure the safety of the students entrusted to them, but even more so about the inability of that school community to recognize and rectify those failings. A close family friend had a prediction during the criminal trial, “Chessy, the assault isn’t what’s going to hurt you the most. It’s the betrayal from friends and people you trust that will have the biggest impact on your life.” She didn’t believe him at first but in the years that have followed the statement has rung true. As an example, Prout says the father of a close friend at St. Paul’s started a fundraising campaign for her rapist’s defense lawyer. Prout insists there are lessons for other schools to take away from her story: “First of all, acknowledge that something bad happened and acknowledge that they’re complicit and acknowledge that they’re wrong. I think recognition and accountability, taking responsibility for the actions of the institution, or the inaction of the institution, I think is paramount to moving forward and making things better. You can’t fix something if you don’t acknowledge that it’s broken.”

No specific mention of the ISSH sexual assault case was made during Prout’s lecture in May — “I think it is still an open wound for the community there” — but she was encouraged by her reception and the open conversations she had with students and administrators. “I hope that something concrete and yearlong can be added to curriculum to really propel this conversation forward.” Prout has taken her own steps towards promoting consent education at a younger age as an ambassador for PAVE (Promoting Awareness, Victim Empowerment). She encourages schools and parents to begin consent conversations “as young as kids can start talking,” in order to ensure children feel a right to their own bodies. That could be as simple as teaching a child how to decline a hug. “Giving kids the language to know how to say no, and to know how to assert their rights really young is so important.”

Since the “Today” show interview, Prout’s role as a public advocate and activist has taken her to schools, military bases, the offices of international banks, a global panel on sexual violence and Capitol Hill, where she addressed lawmakers and also protested with other survivors at the State of the Union. At just 19, her resume could rival those twice her age. Her family has started the I Have the Right To organization based on the book title and hashtag, a phrase Prout hopes can be an “assertion of rights that becomes an empowering rallying call for everyone,” whether someone is asking for a right to affirmative consent, gun safety, DACA or simply compassion. Bound for the all-girls Barnard College in the fall, she hopes to continue juggling her advocacy and activism with full-time studies. Despite this busy schedule, she has found time to take up a new hobby, boxing: “I could never tire of hitting that punching bag.” It’s a release valve, Prout explains, a way to channel the anger she still feels into physical strength. “I had always wanted to take a self-defense class, but then I realized I like self-offense a lot better.”

The I Have the Right To organization can be found at www.ihavetherightto.org.