August 22, 2018

Contesting Myths

Best-selling writer Robert Whiting reviews a history of Japanese “samurai baseball”

“Samurai baseball” is a term used to describe the traditional approach to baseball in Japan, known for its focus on endless training, self-sacrifice and development of spirit. It puts a premium on concepts like gattsu, seishin (spirit), konjo (to have guts) and magokoro (sincerity) as seen in the samurai warrior code of bushido. The basic idea is that a team does not win because its players are bigger and stronger, but rather because it has trained harder than its opponents and exhibits the dedication to work together as a team.

Japan adopted the Western concept of sport in the Meiji period, learning the game of baseball from American professors, and adapted the philosophy of training, practice and sportsmanship from its martial arts past. The function of sport in society became one not to provide leisure and exercise but to “provide mental discipline to create a strong character.”

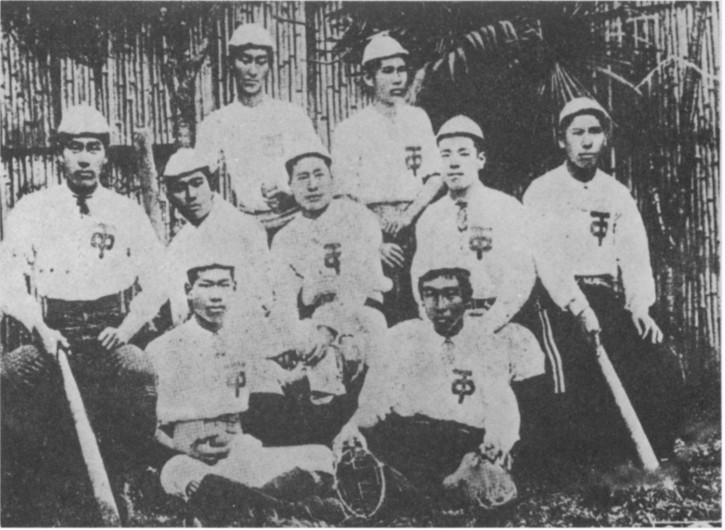

The specific origins of samurai baseball could be found in the First Higher School of Tokyo (now part of the University of Tokyo) which in 1896 defeated a team from YCAC (Yokohama Country & Athletic Club) in a lopsided match — the first formal games ever played between Japanese and American teams — and helped make baseball the national sport of Japan. The majority of the students at Ichiko, as it was known colloquially, came from samurai families and they applied the principles of martial arts onto baseball with a vengeance. As described in the Koryoshi Ichiko Chronicles and other writings, players trained all year, swung the bat 1,000 times a night in the dormitory, and pitchers threw so many curves they had to hang from the cherry trees adjacent to the field to straighten their arms out. It was forbidden to use the word “ouch” because it was considered a sign of weakness ; if you got hit in the nose with a fast ball and it was really painful then you could use the word kayui (itchy).

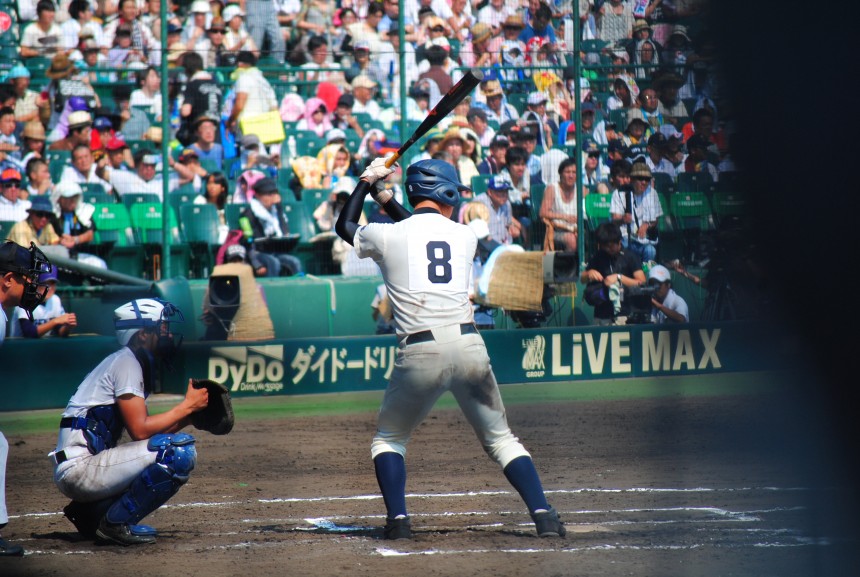

The Ichiko tradition has been carried on in high school baseball in Japan, most importantly in the championship tournaments at the Koshien Stadium near Kobe, where feats of heroic pitching by an ace pitcher on several consecutive days are witnessed annually. It was implanted in university baseball in the 1920’s by Waseda University’s team manager Tobita Suishu, famous for his “shi no renshuu” (death practice), at Meiji University, where the cry of “konjo! konjo!” and midnight practices were the norm, and at Keio University, where a sign read “3,000 swings in the morning, 3,000 swings in the afternoon. If you don’t do that you can’t win.” It was reified in the professional league by the Yomiuri Giants and stars like Sadaharu Oh, who honed his skill by slicing countless sheets of paper suspended from the ceiling with a samurai sword, and Shigeo Nagashima, who slept with his bat and rose in the middle of the night to do shadow swings. Most recently it is found in Ichiro Suzuki, whose domineering father brutally trained him from age seven and told him, “the only way to succeed is to suffer and persevere.” Arguably, no one in Japan or America’s MLB has ever trained harder through the years than Ichiro. His grueling pre-game preparatory routine has been the subject of continual awe to players on opposing teams who stopped to watch.

Hong Kong University Press, March 2018.

Contesting The Myths of Samurai Baseball: Cultural Representations of Japan’s National Pastime by Christopher T. Keaveney, a professor of Japanese at Linfield College Oregon, analyzes the persistent appeal of the samurai baseball myth in Japan, as it has been represented by writers, filmmakers and manga artists throughout the past 150 years, who honor or disdain its traditions.

Keaveney introduces us to a delightful array of characters, starting with Masaoka Shiki, a famed Meiji era poet who defined the modern haiku form but who was also a baseball nut and penned baseball-themed poems in both tanka and haiku forms, celebrating the values of bushido that helped define Japanese baseball literature.

He takes us through Japan’s rich history of films related to baseball, which go back almost as far as the history of baseball itself and include Fumetsu no Nekkyu, a 1955 biopic of famed pitcher Eiji Sawamura, who tamed Babe Ruth and other visiting big-league stars in 1934, but died in WWII when the ship he was on was torpedoed. That film, which had striking similarities to Sam Wood’s Pride of the Yankees, stressed the qualities of magokoro and konjo, which Sawamura possessed in real life. It stood in marked contrast to Masaki Kobayashi’s I Will Buy You, a 1956 film about money and baseball that suggested that the economic realities in the professional game trumped the pure values of bushido that high school and college stars lived by. Nagisa Oshima’s classic, Gishiki, used baseball as a metaphor for Japan’s abandonment of its citizens during the war.

Next, Keaveney guides us through baseball fiction, including juvenile fiction which dates back to the Taisho era. Among the many works he discusses are the 1996 runaway best-selling children’s novel, Battery, by Atsuko Asano, which endorses the value of magokoro and underscores the fundamental virtues associated with bushido of humility and acquiescence to authority; Beat Takeshi’s baseball novel, The God of Sandlot Baseball (1996), about a homeless man who teaches players to have respect for the game; and the Setouchi Shonen Yakyuudan (Setouchi Youth Baseball team) of 1979, a tale of how a baseball game played in 1945 by island residents against a team composed of visiting US soldiers served as a catharsis to help the Japanese public overcome the shock of defeat in war. The book was later made into a film known as MacArthur’s Children abroad.

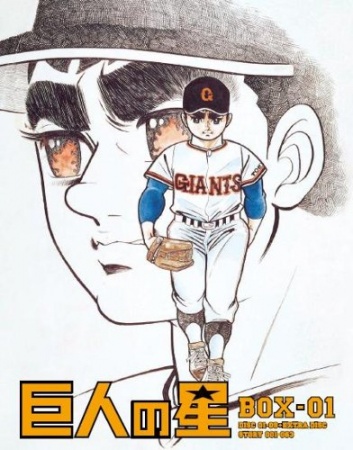

He builds upon this foundation by examining postmodern baseball fiction, including works by Haruki Murakami and other popular Japanese writers and ends with chapters on baseball themes in Japan’s manga and anime, starting with Ikki Kajiwara’s blockbuster Kyojin no Hoshi (Star of the Giants), about how a small boy’s brutal childhood training — he is forced to wear a muscle-building harness of leather and steel spring that restricts his movements to build muscle 24 hours a day, for years — helps him become a winning pitcher who can do magical things with a baseball. Hoshi is contrasted with the manga Dokaben and Abu-sa, both by Shinji Mizushima, which challenged the orthodox samurai values and the prevailing standards of the established baseball manga, and focused on simply having fun playing the game.

Baseball still remains the number one sport in Japan, surviving a challenge from soccer in the early 1990s thanks to the success of Japanese players who migrated to the US to star in MLB, such as Hideo Nomo, Ichiro Suzuki and Hideki Matsui. It’s appeal is enduring. As Keaveney puts it, “There is virtually no one in Japan who is unfamiliar with baseball, its fundamental rules and rhythms.”

The question he asks in this book is, “If baseball continues to appeal to the Japanese, will its appeal be that of the samurai baseball model that has flourished in Japan traditionally or will it be a different model, one closer to the paradigm embraced in the US that differs in fundamental ways from Japanese yakyu?” The US model being one based on individual preferences and initiative and proper rest.

The jury is still out. But if Hidenori Hara’s 2014 popular manga series Vancouver Asahi Squad: A Legend of Samurai Baseball is anything to go by, samurai baseball is alive and well. In the series a team of Japanese-Canadians in 1941, facing internment in a prison camp, confront prejudice and overcome insurmountable odds on their way to winning local and regional championships, using good old-fashioned Japanese gattsu and konjo. (Vancouver Asahi was made into a popular movie).

“It was a nationalistic tribute to the legend of samurai baseball and to the almost religious devotion to practice and discipline that were at the heart of the Ichiko baseball ethos from the beginnings of Japanese baseball,” says Keaveney. “In fact, the descriptions of the Asahi team’s victories over physically larger but less skilled white opponents echoes the victories achieved several decades prior to the story’s action by the famed Ichiko team over American teams in Yokohama. It is by sheer guts and adherence to discipline and teamwork, this manga is saying that David is able to slay Goliath.”

He notes that in June 2016, a new pachinko machine emerged bearing the instantly recognizable image of the hero of Kyojin No Hoshi, holding a flaming baseball with flames shooting from his eyes, along with dramatic scenes from the story.

He might also note that while the pros have softened somewhat, high school baseball demands as much blood and guts as it ever did. Year-round training of five to six hours a day, seven days a week is the norm. A directive from the Japan Sports Agency last year that high school sports teams take two days off a week to rest has, by all accounts, been studiously ignored by the school coaches and players.

Contesting Myths is a well-researched book that will open your eyes to what a rich baseball culture Japan has in film, literature and manga, one that in many ways is superior to that of the US, which of course has its own such traditions — The Natural, Field of Dreams, et al. For example, I Will Buy You predated Brad Pitt’s Moneyball by more than half a century. The animated series version of Kyojin No Hoshi exceeds anything that Hollywood has ever done in terms of excellence, scale and pathos.

I have developed a serious aversion to academic writings on Japanese baseball over the years. So much of it is tedious, pompous and devoid of common sense. The 2002 Guttmann-Thompson book Japanese Sports: A History, to cite one example among the many which spring to mind, devotes pages to the ancient game of kemari but not even a brief introduction to the wildly popular Koshien High School Baseball tourney. Chris Keaveney’s book, however, is a glowing exception.