January 28, 2026

Hay Fever in Japan: Mother Nature’s Revenge

How a postwar decision brought upon the hay fever epidemic

By Mike Smith

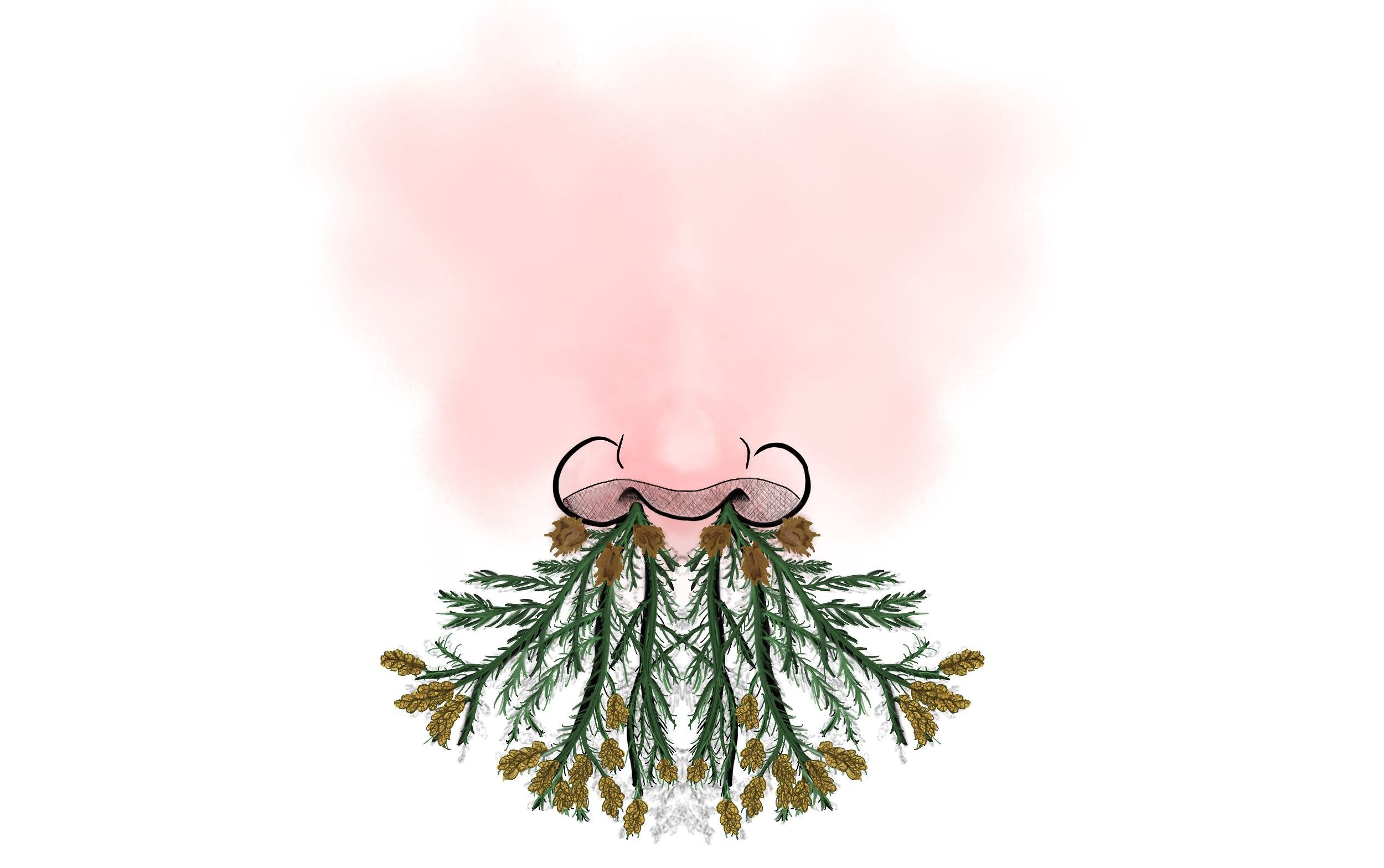

They say you either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain. For sugi (Japanese cedar) and hinoki (Japanese cypress), the main culprits for Japan’s nationwide hay fever problem, this statement couldn’t be more true.

If you’ve ever lived in Japan, you might know this feeling: It’s late February, you’re giddy that spring is just around the corner. Yearning for the simple joys of warmer days, sipping Strong Zeros under sakura (cherry blossoms) and basking in a much-needed break from hearing “Samui desu ne” (“It’s cold!”) any time you step outside. When suddenly your nose is violated by an organism’s reproductive powder without consent. Powder which could have come from further than 100 kilometers away.

As your sinuses begin to feel pressure akin to that of the Mariana Trench and your nose starts running like Usain Bolt, you think to yourself: Why me? Why now? Maybe you’ve been living in Japan for a few years now with no allergies. So where is this so suddenly coming from? How can I free myself of this misery?

The Root of the Problem

Well, to answer these questions and more, we must first go back in time to World War II with the help of Kunio and Kaoru Kikuchi. They are second-generation owners of a wholesale lumber company based in Koto-ku. Kunio is also a board member of the Tokyo Lumber Wholesale Cooperative, and Kaoru volunteers as a tour guide at the Fukagawa Edo Museum.

According to Kunio, the demand for lumber to use in construction and as fuel was at an all-time high during the war, resulting in massive deforestation across Japan’s natural broadleaf forests. On top of that, the bombings of Tokyo by the United States Army Air Forces wiped out many parts of the city and left millions homeless, meaning material was desperately needed for reconstruction.

As the war came to an end in 1945, the recovery of the nation was at the forefront, leaving the Japanese government to solve three major issues: rejuvenating the economy, rebuilding infrastructure and reviving the now stripped-bare countryside.

Well, to build buildings, you need lumber; to get lumber you need a workforce to cut down and replace the trees and to keep a workforce going and jump-start the economy, you have to pay them.

It just so happens that the sugi and hinoki trees, which are native to Japan, not only grow super quickly but are also disease-resistant and evergreen. Perfect candidates for trees to replant as they cut more trees, right? Or at least that’s what the government thought.

For more stories on life in Japan, also check out:

According to Kaoru, the lumber industry has always been a big part of Koto-ku. However, it wasn’t until after WWII that the industry skyrocketed. “My father returned from fighting in the Pacific War to a Tokyo that was burnt to the ground, and he needed to find a way to make money,” she says. “With the help of his father, they started this company, seeing that the demand for quality lumber was high.

However, sugi and hinoki were not popular for lumber companies to sell. It was more cost-efficient to import lumber from Southeast Asia. It was cheaper to buy and grew larger, faster.”

As time passed, Japan recovered from the war with an improved infrastructure, a stronger economy and forests filled with the newly planted trees. So many new trees that, according to Japan’s Forestry Agency, sugi and hinoki now make up around 40 percent of the country’s forests due to the aggressive postwar forestation policies.

“Technology continued to advance and the desire for fire-resistant housing increased in the city, there became less of a need for genuine wood as a construction material,” said Kunio. “So the trees remained untouched over the years.”

Keep it in Your Plants

Unlike humans, who hit puberty in their teens, sugi and hinoki don’t reach sexual maturity until about 30 years old, which is when they release their greatest amount of pollen.

It only makes sense that before the 80s, when the trees were still relatively harmless saplings, widespread cases of hay fever were unheard of. According to a 2014 study by Dr. Yozo Saito, the medical advisor at Kamio Memorial Hospital, the rate of patients suffering from sugi pollen was in correlation with the dispersal amount from trees. The number of patients in the Tokyo metropolitan area affected by hay fever increased 10 percent from 1983 to 1987, 19.4 percent in 1996 and 28.2 percent in 2006.

With all this information, it’s hard not to think that Japan’s trees are out to get us, maybe as some type of revenge plot for global warming. However, Dr. Yushi Washio, an otorhinolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat specialist), is here to put us all at ease. He’s been running his own clinic for almost a decade and is a member of the Japanese Society of Allergology.

“Pollen itself isn’t bad for the human body,” Washio says. “It’s when your immune system overreacts to the pollen that it causes the symptoms.

“Imagine your body’s tolerance to a certain allergen as a cup of water. Each time that allergen is introduced to your body, more water is added. Eventually the cup cannot hold any more water and that’s when the symptoms start. Each person’s cup is a different size and that’s why our bodies’ reaction timings to allergens vary.”

As for which allergens, it depends on your location. For the U.S., grass and ragweed pollen are common culprits; in Europe, it’s birch trees.

“Sugi is very tall compared to other countries’ pollen factories,” Washio adds. “Its pollen can easily fly from Shikoku to Hyogo.”

If you don’t have a map ready, that’s easily over 100 kilometers, which goes to show that you’re never truly safe from the dastardly yellow powder, even in your highrise tower in Shibuya.

“If you’re living in Tokyo, your exposure to pollen is lower than that of someone who might live more in the suburbs,” says Washio. “But, due to the hard surfaces of the city, pollen can reenter the air easier than it could on soil. Studies have also shown that high levels of pollution in downtown areas can exacerbate allergies.” While it may seem like all doom and gloom, there is one way to provide some relief to those suffering from this annual nightmare: Preparation.

“Pollen allergies can affect everyone, regardless of race,” says Washio. “It’s best to visit a doctor to learn about how your own body deals with allergies. It’s not like catching a cold. “Hay fever is chronic. People have allergies 365 days a year; they just aren’t exposed to pollen during all seasons. It’s best to prepare. If you know you will struggle with allergies in the spring, start taking medicine ahead of time.”

As we look to the future with our newfound knowledge, one can’t help but notice another recurring problem: Japan discovers an issue, finds a quick fix and future generations deal with the repercussions later.

We saw this with the monoculture reforestation of sugi and hinoki, which is causing nationwide health issues 30 years on. And again, going way back in time, with the feudal military government stopping the rise of religious ideology during the sakoku (closed country) period, only to have to play catch up with the rest of the industrial world 200 years later.

Check out our full guide on how to buy medicine for hay fever in Japan

If you suffer from allergies and want to find help, check out this link for the Bureau of Social Welfare and Public Health’s resource page.

Originally published March 2021, updated January 2026.