January 17, 2020

Beyond Sushi and Karate

Little-known and interesting Japanese loanwords in English

With the rise of Japanese popular culture worldwide, languages around the globe are using more and more words from the Japanese language. In fact, there are quite a few words in normal English conversation that you probably didn’t know come directly from Japanese.

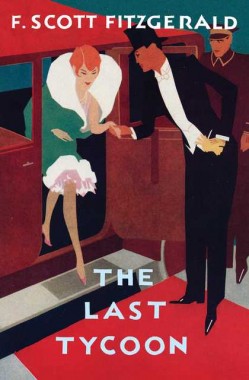

Tycoon

In English, we use the word “tycoon” to refer to business magnates, entrepreneurs, and real estate moguls who have acquired a large and diverse empire of revenue. The term has been applied to the likes of Donald Trump, Oprah Winfrey and Warren Buffet.

It conveys a sense of established power and entrenched wealth — probably because it comes from the Tokugawa-era shogunate, who coined the term. Properly rendered in romaji as taikun, it roughly means “supreme leader” and was used to mark the shogunate as Japanese commanders who wielded the true power of the state, while still respecting the imperial family by avoiding any terminology that would imply royalty.

The word was brought back to the U.S. by Commodore Perry in his travel journals concerning his voyages to Japan and India. From there, it was picked up by a high-ranking aide of Abraham Lincoln, John Hay, who used the term to refer to the president in his own diaries. From there, the term began to leak into common parlance and became associated with the financially powerful.

Emoji

Emoji are ubiquitous in the West, sold on T-shirts, lending their likeness to pillows and even starring in major motion pictures. This term, brought over from Japan, is a combination of the English term “emotion” and the Japanese word for character, ji.

The Japanese origins of emoji can be glimpsed from some of the more obscure emoticons offered on modern smartphones. Upon a closer inspection, specific aspects of Japanese culture are overrepresented in the library. Scrolling through the syllabary, users can find symbols for senbei (rice crackers), hanami dango (sweet dumplings) and hina dolls left over from emoji’s early origins as a Japan-centric phenomenon. More modern characters have been selected for universality across cultures.

Head Honcho

Have you ever heard someone referred to as the “head honcho?” In America, the term is used informally to refer to the highest-ranking member of a group or organization. It can be used in reference to professional status — referring to the president of a company or a person retaining a political office — or it can be used informally to refer to someone respected within a community or with a universally recognized sense of seniority.

This word was derived from the Japanese hancho, the word for the leader of a group of people. Hancho can be used in a variety of situations, formally or informally. Children can use it when assigned as group leaders, or it can be used in certain squads related to combat or the military. The term was brought back to America by occupying forces post-World War II.

Kawaii

Growing up in the early 2000’s online, it was impossible to go on sites with members of your own age group and not be bombarded with broken Japanese lingo ripped from the subtitles of the most popular anime shows of the time.

Kawaii is one such word that dominated online pop culture communities for seemingly half a decade. This word is noteworthy in that many of the young teenagers using it were not entirely familiar with its pronunciation, often failing to hit the final “i” syllable.

Senpai

Senpai as a joking or intentionally out-of-place title in English conversation gained popularity around the same time as kawaii, and with the same audience. But senpai has had a much more heuristic and measured growth. Outgrowing its humble anime-fan origins, the word senpai began to seep into mainstream popular culture, being used on the critically-acclaimed TV comedy “30 Rock.” If anything, the word is more popular in 2019 than it has ever been before.

Kimono

Not all words have landed on foreign shores completely intact, however. Much like the wasei-eigo (Japanese pseudo-anglicisms) that foreigners find so amusing, borrowing Japanese loanwords can get quite mangled.

Kimono, a universally understood term to mean, at the very least, Japanese robe, has been dumbed down by Western fashion industries to the point that the term is almost meaningless in its current usage. Putting aside last year’s infamous Kardashian #KimOhNo controversy, fast fashion has used the term to describe open, blouse-like tops and short, silk bath-style robes for years.

Sake

Sake is another prime example. Conversations between Japanese native and foreign beginners in the language can be difficult at bars and pubs when word is used. In America, sake (pronounced with a baffling “i” sound at the end) refers only to Japanese rice liquor, despite the original Japanese term referring to any and all alcoholic beverages.

For many foreigners living in Japan, it can be easy to see misuses of Western languages as an amusing oddity of Japanese culture. But the truth is, other countries should be careful before pointing the finger.

They’re just as guilty at times of loving a word so much they don’t even care what it really means.