November 16, 2020

Scientific Literature About an Unscientific World

Kanji Hanawa divulges society’s absurdity in two translated novellas

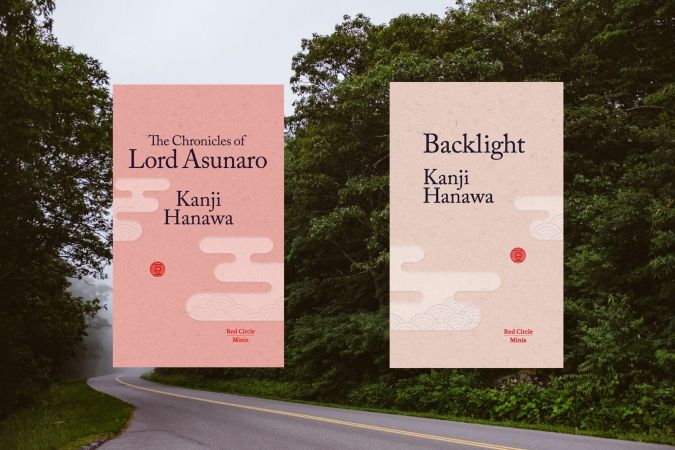

When two novellas by Kanji Hanawa were published in English, it was a long time coming. Literally hundreds of short stories and novellas in Japanese, the occasional magazine and compilation translation in English, and two prestigious Akutagawa Prize shortlists later, Hanawa’s “Backlight” and “The Chronicles of Lord Asunaro” live in English. These fresh books immerse a reader in Hanawa’s uniquely Japanese rendering of psychology and individualism, while thrilling with the settings of the Hokkaido wilds and Edo-period Japan.

Unflinching scientific analysis, curious incidents that can be found only in Japan, and mischievous humor collide to create two worthy novellas and a significant catalog of work

“His narratives often expose the pressures and challenges of life in Japan,” says Richard Nathan, translator of “Backlight” and a founder of Red Circle Books, the publisher of both of these novellas. “He often creates situations designed to mock or shine a humorous light on how people behave or are compelled to behave in Japanese society. The nightmares of modern life if you like.”

Hanawa explores society’s absurdity with precise, almost eager curiosity. In “Backlight,” a small group of scholars try to determine what happened in the case of a missing boy in Hokkaido. After misbehaving, a young boy was put out on the roadside by his parents as a punishment, but when they returned for him just a few minutes later, he had vanished.

A wide search for the boy spirals out of control into a massive international headline, while the professors examine psychology, sociology, philosophy and the physics of survival, using all of the argumentative methods at their disposal to determine just what had happened.

“Animals leave their offspring to fend for themselves, and only the tough ones survive… If that is the case, it was a subconscious gambit by the parents, creating a stage for them to act out the abandonment,” the scholars in the fiction discuss.

“The father did it to [the boy] meaning to teach him that sometimes things like this happen in life. But [the boy] only saw it as callous, and in revenge wanted to do something to upset his father.”

“Maybe abandonment, and the fear of it, is the force of will that powers our hearts,” another scholar says.

This academic dialogue is more light-hearted philosophy than dense analysis, and the way the professors leap through the hoops of every available theory in search of an explanation feels as absurd as it does profound.

Elsewhere on Metropolis:

- Five (Translated) Japanese Novels to Read in 2020

- Yukio Mishima: The Resurgence of a Japanese Literary Master

- The Titanic Literary Accomplishment of Yoko Ogawa

- Meiko Kawakami: Breasts, Eggs and Existential Feminism

“Translating these conversations so that they read smoothly and naturally in English, while also sounding authentic in terms of how Japanese academics might speak and how the author is trying to portray them or perhaps at times mock them is a very hard balance to attain,” Nathan says.

By the time the boy is found, the truth of what happened seems to eclipse even the most carefully thought-out theory, making for a fascinating exploration of a real-life event.

If “Backlight” is a scientific examination of an unscientific event in modern Japan, “The Chronicles of Lord Asunaro,” translated by Meredith McKinney, is a scientific examination of a particularly unscientific man in the Edo period. Packed with vivid period detail, “Chronicles” tells the life and (mis)adventures of the fiery, sexually prodigious and arguably unhinged Lord Asunaro.

The story follows Asunaro from childhood to death, zooming in on curious circumstances or notable tales, such as when a preteen Asunaro viciously bites his retainer’s ear when bored during Confucian lessons, and his clumsy but impassioned courtship of an older noble girl via poetry.

View this post on Instagram

A playfulness and humor also thrives in Hanawa’s writing. “Small though his brain might be, his height was considerable,” the narrator comments on Asunaro, whose antics run the narrow gauntlet between amusing and deeply disturbing.

Asunaro’s pampering, misbehavior and entitlement, while also unquestionably accepting his duties to his father and the shogun make for a unique lens into the psychology and life of the upper class of Japan’s Edo period. The sheer amount of precise historical detail, explained in light, playful prose, makes the quick read worthwhile.

[Hanawa’s] narratives often expose the pressures and challenges of life in Japan

— Richard Nathan, translator of “Backlight”

“There is certainly a rebellious mischievousness to him and his works,” Nathan says. “His use of language is very clever, at times complex, and he is often intentionally ambiguous as he isn’t the type of author who likes to spell out everything clearly.”

Translating Hanawa’s voice is a challenge, but close collaboration between Hanawa and the editorial team allowed for more communication than is typical between author and translator. “As our Red Circle Minis are originals and we are in direct contact with our authors, we have the ability to ask each author questions,” Nathan says. “Kanji Hanawa was proactive and very helpful with both of his books.”

While some of Hanawa’s writing had been translated previously in collections, these are his first two novellas to be published as independent books. Red Circle’s decision to translate Hanawa came after Nathan met Hanawa in Japan, leading Hanawa to decide to write about the news story of the disappearance of a 7-year-old boy when it came up in conversation — which turned into the story “Backlight.”

“It takes considerable time and serendipity to meet, select and find our authors,” Nathan says. “Our aim is to grow our curated circle of authors to around a dozen writers, ending up with a diverse mix of ages, genres and genders that reflect the many narratives of Japan.”

Hanawa was also a professor of French literature and a translator of the French philosopher Paul Nizan, as well as children’s books. His influences ranged from the French poet Arthur Rimbaud to Ryoma Sakamoto, a leading figure behind Japan’s movement towards the Meiji Restoration in the 1850s and 1860s.

Both “Backlight” and “The Chronicles of Lord Asunaro” are refreshingly brief novellas, vignettes into one of Japan’s biggest international human interest stories in the last few years and a history that is often romanticized but rarely unpacked. Hanawa’s writing does a heck of a lot of unpacking.

Readers who want insight into the depths of Japanese culture will enjoy Hanawa’s works. Unflinching scientific analysis, curious incidents that can be found only in Japan, and mischievous humor collide to create two worthy novellas and a significant catalog of work.

Kanji Hanawa passed away earlier this year.

The English translations of “Backlight” and “The Chronicles of Lord Asunaro” are available on Amazon, Waterstones and other sites.