April 1, 2025

Kiyoshi Awazu and the Reinvention of Contemporary Japanese Aesthetics

An emblematic figure of Japanese graphic design

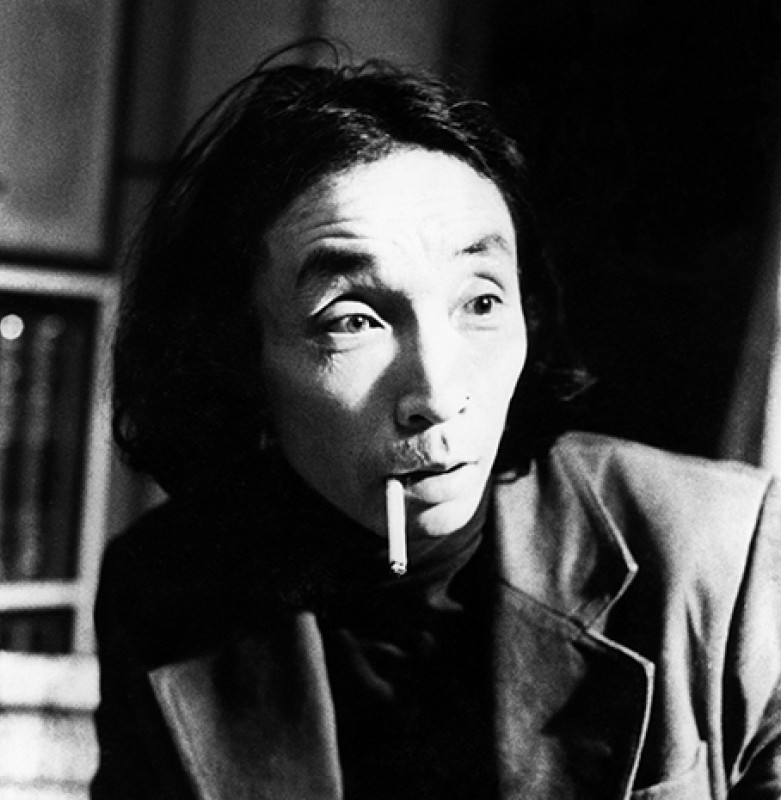

“I wonder where the imagination for drawing comes from. On a sheet of white paper, I casually draw a line. The white paper immediately becomes a screen and a space. Sitting in front of the paper, I wait for my imagination to visit. My imagination should be clearer than when I meditate. Otherwise, I can’t draw.” This is the state of mind of Kiyoshi Awazu, an emblematic figure in the history of Japanese graphic design. A singular, multifaceted, committed artist, creator of countless posters, celebrated for his contributions to cinema and urban design, he is considered one of the pioneers of the revival of graphic design.

The experimentation in post-war Japan

Born in 1929, Kiyoshi Awazu grew up in an imperial Japan where art was used for propaganda purposes, before witnessing, as a teenager, the capitulation of his country in 1945. This event marked the end of a militarist regime and the beginning of the American occupation, and profoundly disrupted artistic production. Awazu belongs to this generation of creators who refuse the old order and seek to redefine Japanese aesthetics through a new prism, freed from nationalist ideology and imbued with social concerns. In this context, graphics become an essential field of experimentation.

Since the 1950s, many Japanese creators have invested in the field of posters, advertising design and publishing. The artists are particularly inspired by Western avant-garde movements such as Bauhaus, surrealism and constructivism. Kiyoshi Awazu’s approach consists of diverting and merging these influences with a graphic vocabulary inspired by traditional Japanese arts. His vision is based on a desire to reinterpret the visual history of his country, to transcend it to create a unique, immediately recognizable language.

First hired as a graphic designer in the advertising department of the Nikkatsu film studios, he became familiar with the world of images by creating film posters. Commissioned work allows him to develop a personal aesthetic, both expressive and symbolic. At a time when Japanese advertising graphics still followed classic patterns, inspired by Western realism, Awazu dared to experiment. He introduced abstract elements, bright colors and fragmented shapes infusing his works with an unprecedented evocative power.

“Awaken the past, recall the outdated”

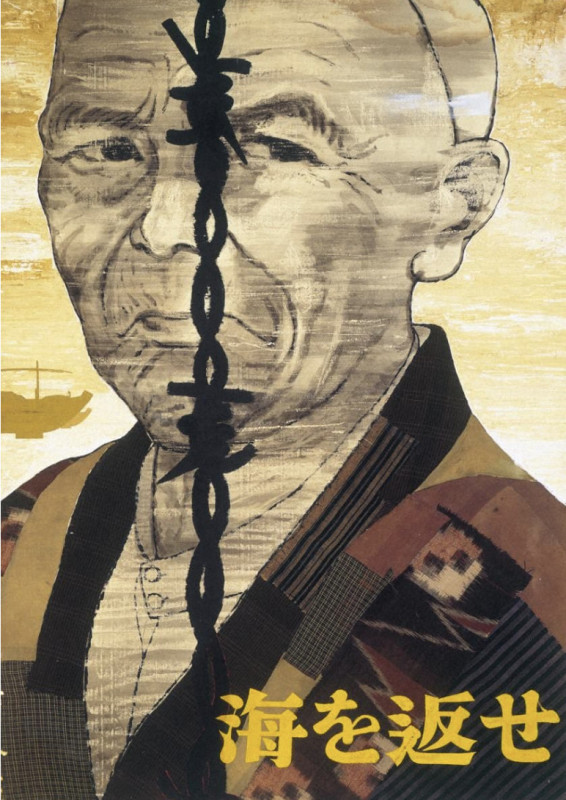

The first decisive turning point in his career came in 1955 when his poster Give Our Sea Back earned him recognition from the Japan Advertising Artists Club. This work, depicting an angry fisherman protesting the American occupation of Japanese waters, marks a key moment in the country’s graphic design history. Not only did it affirm the political dimension of Awazu’s work, but it also embodied a stylistic break. Rather than adopting a realistic or academic approach, he favored symbolic and impactful iconography, mixing expressive calligraphy, dynamic compositions and references to ukiyo-e prints.

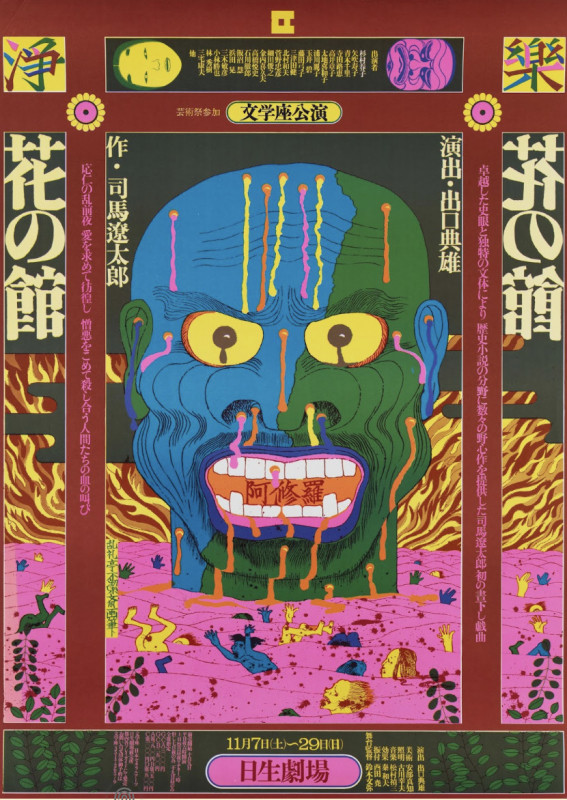

Through his graphics, Awazu rejected the functional minimalism of Western modernism, which he considered to be a visual standardization devoid of soul. Graphic design must be an act of memory as much as a creative gesture, or in his words: “Awaken the past, recall the outdated.”. This desire to reinterpret Japanese cultural heritage is a constant in his work, which borrows both from the decorative motifs of the Edo period and from the aesthetic principles of Noh and Kabuki theater.

In 1964, Awazu designed the poster for the 4th International Print Biennial in Tokyo. That year’s edition highlighted the work of Hiroshige Utagawa (1797-1858), giving Awazu the chance to pay homage to the artist who came before him and the ukiyo-e tradition. This Edo-period Japanese artistic movement was known for its mass-produced woodblock prints. Hiroshige’s paintings generally depict panoramic views of Japan, emphasizing the relationship between nature and human life, between the picturesque hills and the city built there. By integrating the work of the master into his own artistic conception, Awazu made it more modern, more abstract, and conveyed a fundamental humanist voice in his work.

Removing borders and distinctions

“In all areas of expression, I am committed to breaking down not only the boundaries between forms of expression, but also the class, the category, the disparity and the high and low that have appeared in art.”. Awazu behaves as an artist engaged in society, using art as a means to promote social and political justice, illustrating those who struggle and seek dignity. His paintings focus on common people, workers, the disadvantaged and those excluded from society.

The artist’s varied expertise allows him to take part in projects on which he partners with other creators. In 1969, he won a Japan Academy Award for artistic direction of the film Double Suicide, directed by Masahiro Shinoda. The poster he created for the film won the silver prize at the Warsaw International Poster Biennale in 1970, earning him praise abroad. He was also the set designer for films Pitfall (1962), and Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974), selected in competition at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival.

Another exceptional collaboration in Awazu’s career was with architect Minoru Takeyama on the Nibankan Building (1970). The building is located in Tokyo’s Kabukicho entertainment district, and is a symbol of architectural post-modernism. Formed from several volumes that develop from a common platform, the building reflects the chaotic nature of Tokyo’s environment. The geometric richness comes from Kiyoshi Awazu’s inventive graphic work, consisting of patterns, lines, commercial signs and vibrant colors, making the complex an interesting example of a commercial facility hosting bars and saunas.

In more than sixty years of activity, Kiyoshi Awazu has built a reputation for experimenting with a wide range of visual formats. He pioneered a new world for graphic design, with psychedelic symbolism and political advocacy that left an indelible mark on the history of Japanese art. From paintings to posters, from cinema to architecture, his creative passion knows no boundaries––he questions not only images and the act of communication but also human existence in its entirety. Clairvoyance and the totality of his creative activity still have a major impact today.