April 2, 2025

Sento Architect Kentaro Imai and the Art of Bathing Spaces

The architecture mastermind behind today’s sento boom

This article was originally published in Metropolis Magazine, “Designing the City,” Spring 2025. Read the full issue here.

A cold, un-spring-like March day in Tokyo. Fingers numbly flick across a smartphone screen, navigating the way to a tucked-away building in a residential district. Its modest facade blends into the surroundings, but inside lies exactly what I need right now—a sento.

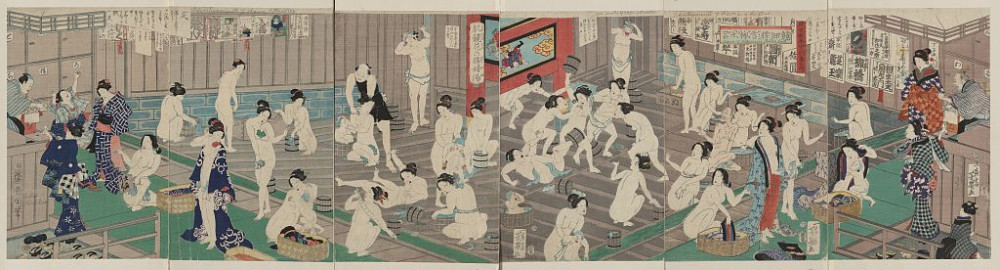

Once a staple of every Japanese neighborhood, the number of public bathhouses declined as home bathtubs became standard. But interest in their charm has not. Sento culture is not merely surviving; in many ways, it is evolving.

As I lower myself into the steaming water, I take in the details of the space—from the painting of Mt. Fuji to the placement of showers. These elements aren’t incidental; they are intentional. And behind many of today’s most thoughtfully designed sento is the architect Kentaro Imai.

Sitting in the water, I find myself thinking back to my conversation with him—the man Japanese media calls the mastermind behind today’s sento revival and a leading figure in the “designers’ sento” movement, a term loosely used to describe both newly built and renovated bathhouses with style.

I had the privilege of meeting Imai recently in his office in Akasaka. As I opened up the conversation, naively, I asked what his favorite sento was—after all, who wouldn’t want to know the go-to spot of a sento architect? He replied after a pause, “It’s difficult to say which is my favorite, but if anything, it’s just the one I go to most often—the one closest to my house.”

His answer perfectly encapsulates what sento has always been. People simply went to their neighborhood sento. Today, because they are so sparsely located, Imai is one of the lucky ones who has a neighborhood sento that he can call his favorite.

Many people now take trains to visit different sento, meeting friends from across the city, and even following Instagram accounts dedicated to sento recommendations. For the most part, sento have evolved from a neighborhood necessity to a destination, chosen for their design, facilities and atmosphere.

Now, a sento needs to be a destination in itself, and this is where Imai’s work shines. His designs give bathhouses a reason to exist beyond routine. I still remember my surprise when I realized that all the sento I had saved on Google Maps were designed by the same person.

The Sento Architect

Imai told me he had always been drawn to art—in fact, he actually went to art school. As a young traveler, he loved discovering new places, but seeing Gaudí’s work in Spain was a turning point—it left a lasting impression and set him on the path to architecture. In his mid-twenties, while working as an assistant at an architecture firm, he lived in a cheap, bath-less apartment in Tokyo. That meant regular trips to the local sento, where he realized nothing else could help him unwind in the same way—and soon, it became an obsession. Once he set his sights on working with bathhouses, those trips turned into fieldwork. He began visiting numerous sento, observing, analyzing and sketching.

In 2000, an unexpected opportunity led him to publish his observations in a column series for 1010, a free magazine by the Tokyo Public Bathhouse Association. Titled Kentaro’s Dream Sento, the series caught the attention of the owner of Taihei-yu in Adachi, ultimately leading to his first commission in 2001.

When I asked him about his most memorable project, he thought for a moment before answering. “It’s not something I can single out—all my works hold significance in different ways,” he said. “But I still have a deep appreciation for my first commission, Taihei-yu, and the owner who took a chance on me when I had no portfolio of sento architecture.”

During our conversation in his office, he pulled out thick files—detailed reports from his research before designing each sento. He studies everything: the neighborhood, the nearest sento and other facilities, demographics, geography, cultural history, etc… His fieldwork is meticulous, and through careful analysis, he comes up with the concept. Branding, strategy and creative direction—elements that might seem beyond an architect’s role—are all part of his process. This is why every sento he designs is distinct, shaped by the essence of its surroundings.

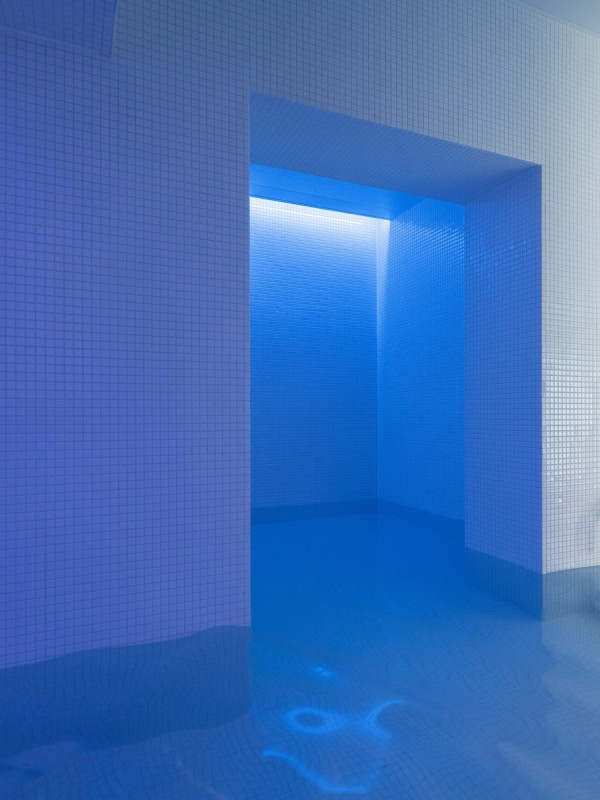

Kairyo-yu in Shibuya embraces the area’s culture with a black-themed, chic interior that doubles as an art space. Mannen-yu in Shin-Okubo, hidden off the main road, has a rustic, retreat-like feel. Mikoku-yu, though housed in a modern multi-story building, reflects the Edo-era aesthetics of the Sumida area. Corridor-No-Yu in Ginza is entirely different—bathed in soft blue light reflecting off white tiles, it feels like a sci-fi dreamscape, meditative like float therapy (but don’t float—it’s bad manners!).

Having visited these sento myself and speaking with Imai, it became clear that the way each sento evokes a distinct sense of space was no coincidence, but the result of his creative vision.

From Sento in Tokyo to Abano in Tbilisi

Travel set him on the path to architecture, and Imai’s love for it hasn’t faded. When I saw that Imai had recently visited the Caucasus nation of Georgia, I was especially eager to hear about his trip.

Back in high school in the US, I had a Georgian classmate who was tired of his American peers thinking he was either Russian or from the state of Georgia. The classmate appreciated that I knew where he was actually from, but more than that, we bonded over something unexpected—our shared appreciation for public baths in both countries, spending hours talking about it.

Imai had, in fact, visited the bathhouses in Tbilisi and shared a sobering observation—many of the old-school facilities are disappearing. “If you want to see the culture, you should go soon,” he told me.

But what struck him most wasn’t just the decline—it was the architectural structure itself. The layout, the flow of movement—it was almost identical to Japanese sento. You enter the changing room, move into the wet area with washing stations first, then the bath. The building is symmetrical, with a central wall dividing the genders and high ceilings letting the steam rise.

Whether in Tokyo or Tbilisi, the logic of public bathing feels almost universal.

Bathing Spaces Beyond Japan

Imai’s work, too, is beginning to expand beyond national borders. In 2023, he designed a Japanese-style bathhouse for a Taipei gym, reinterpreting ryokan bathing culture in a modern wellness space. Taiwan, with its deep interest in Japanese culture, proved to be an ideal starting point for exporting sento culture.

For Imai, this is just one example of how public bathing spaces adapt and evolve across cultures. He isn’t bound by one location—his fascination lies in what he calls yu-kukan (hot water spaces), whether it’s a sulfur bathhouse in Tbilisi, a Turkish hamam, a Roman thermae or the sento I’m stepping out of.

The bathhouse door slides shut behind me. I see a group of friends laughing over bottles of milk, a family of international visitors wearing looks of quiet accomplishment, and a salaryman, his tie loosened, heading back into the night. Sento, as Imai sees them, aren’t just places to cleanse—they are spaces for community, wellness and cultural connection. The conversation with Imai was a reminder that design and architecture could be what helps carry its relevance beyond Japan.

Soak up even more on sento with these related reads:

・How to Use a Sento or Onsen in Japan

・Tattoo-Friendly Sento with Saunas in Tokyo

・Based in Japan: Labianna Pinklady Joroe