May 5, 2023

Seoul Revisited: Finding Retro Japanese Architecture in Korea

Buildings and Memory in Early 20th-Century Korea

By Metropolis

Originally published on metropolis.co.jp on May 2005

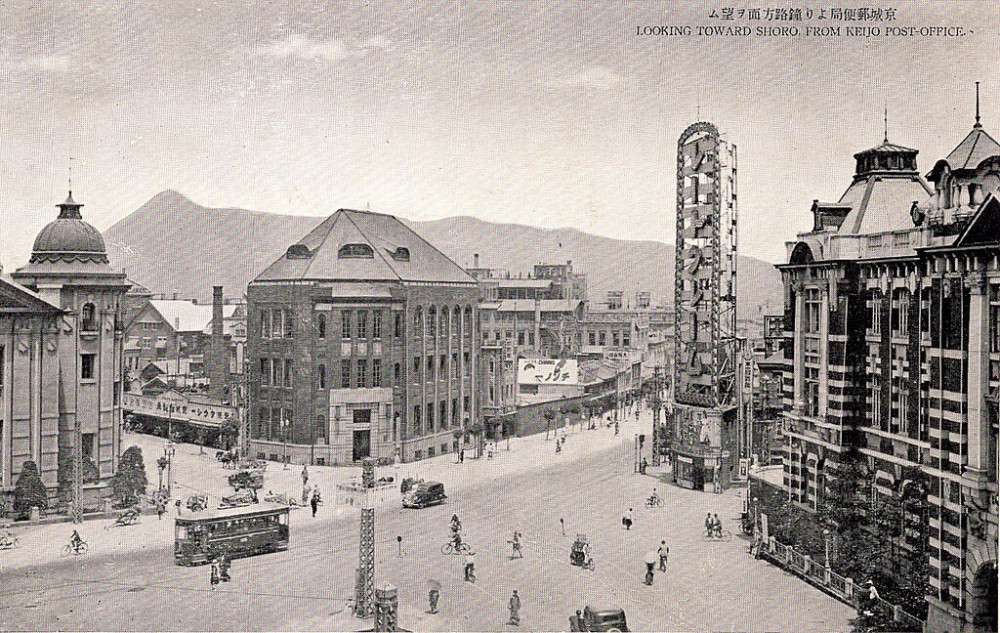

A Visitor’s Guide to Seoul’s Colonial-Era Buildings

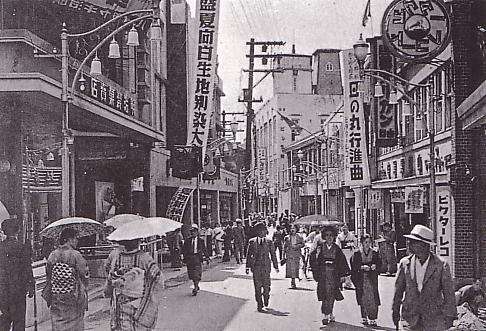

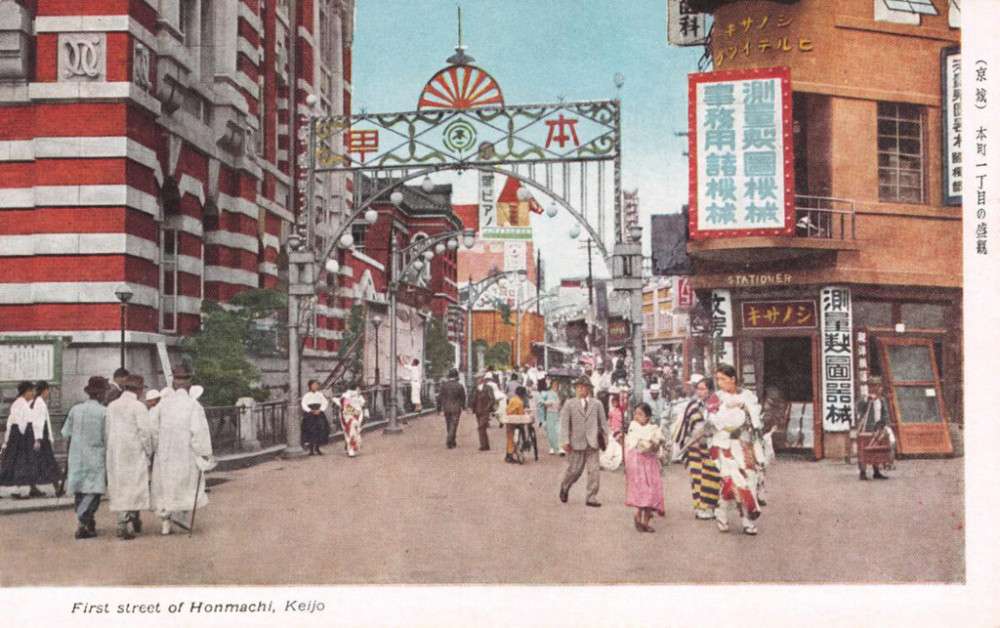

Seoul is a popular getaway for Tokyoites, just two hours away by plane. The South Korean capital is a city of contrasts: futuristic glass towers and LED-lit billboards rise over quiet palace courtyards and tiled hanok alleys. But look closer, and you’ll find another layer, a collection of early 20th-century buildings that once symbolized Japanese colonial rule, now reimagined as cultural spaces, museums, and theaters.

Like the Portuguese churches of Macau, the French villas of Hanoi, Spanish streets of Manila, these structures sit uneasily in history yet lend the city a retro charm that locals and travelers alike are drawn to photograph and rediscover.

1) Old Seoul Station

Opened in 1925, the old Seoul Station was designed by Yasushi Tsukamoto in a mix of Renaissance and Baroque styles, topped with distinctive copper Byzantine-style domes and framed by elegant arched windows. Today it houses Culture Station Seoul 284, an exhibition hall where contemporary art interacts with the building’s stately grandeur.

43-203 Dongja-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul

2) Bank of Korea Money Museum & Annex

The 1912 neoclassical Bank of Korea building, designed by Kingo Tatsuno, still dominates central Seoul with its heavy stone and monumental columns. Inside, the Money Museum explores Korea’s financial history. Next door, the former Tokyo Fire & Marine Insurance Company branch (today the Bank of Korea annex), designed by Jin Watanabe, adds another layer of early-modern detail to the area.

3) The Heritage, Shinsegae

Originally built in 1935 as the Japanese-run Chosen Savings Bank, this neo-Baroque stone structure stands just across from the Bank of Korea. Designed by Kingo Hirabayashi, its symmetry and sober neoclassical details exude turn-of-the-century solidity. Later renamed Korea First Bank, the building was eventually acquired by Hong Kong–based Standard Chartered. In 2025, Shinsegae transformed it into The Heritage is a luxury annex to the adjacent flagship department store, which was also built during the colonial period. Today it serves as a hub of high-end shopping and dining. The building remains one of central Seoul’s most elegant retro landmarks.

Credit: unknown (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

42 Namdaemun-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul

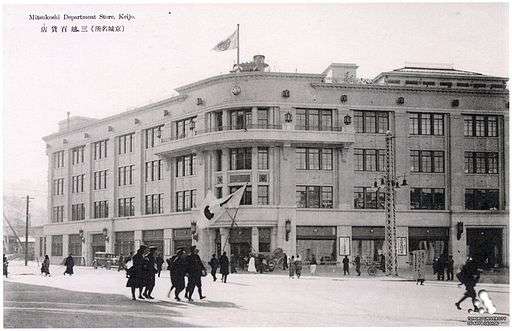

4) Shinsegae Department Store

Opened in 1930 as the Mitsukoshi Department Store, it catered to the city’s elites. After liberation, the building was occupied by the U.S. military for several decades before becoming Shinsegae. While shopping inside feels ultra-modern, the 1930s exterior remains a striking example of early-modern consumer architecture, comparable to flagship stores in old Tokyo or Shanghai.

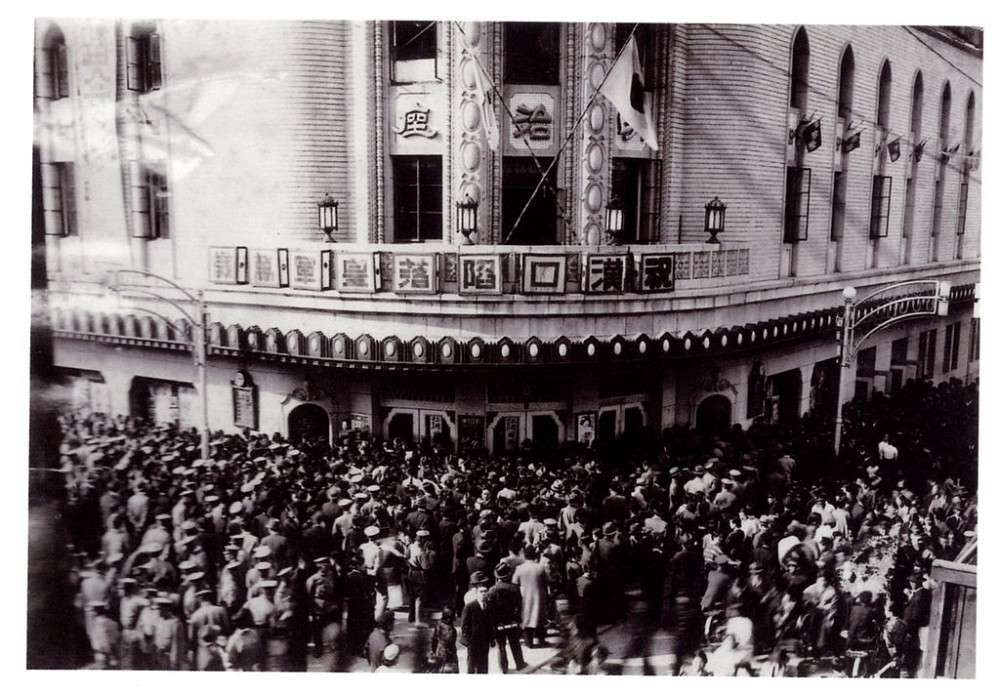

5) Myeongdong Theater

This 1936 Art Deco theater was once the centerpiece of Seoul’s entertainment scene. Reopened after extensive renovation, Myeongdong Theater now hosts plays and performances in a space where curved lines, geometric motifs, and vintage interiors still whisper of its glamorous past.

Credit: unknown (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

35 Myeongdong-gil, Jung-gu, Seoul

6) Ilmin Museum of Art

Formerly home to the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper, this 1920s office block was converted into a museum in the 1990s. Its stone façade and restrained lines embody the pragmatic yet stylish modernism of the era. Today, its galleries of contemporary art highlight how Seoul continues to reinterpret its architectural past.

152 Sejong-daero, Jongno-gu, Seoul

7) KEPCO Building

Built in 1928 as the headquarters of the Japanese-run Keijo Electric Company, this was the first building in Seoul to feature an elevator and more than 580 electric lights. Later taken over by the Korea Electric Power Corporation, it was designated as Korea’s First Registered Cultural Property. It remains a touchstone in understanding Seoul’s early infrastructure and urban transformation.

92 Namdaemun-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul

8) Daehan Hospital, Seoul National University

Korea’s first modern hospital, Daehan Hospital, was completed in 1907 during the final years of the Korean Empire, with Japanese involvement after 1905. Designed by Kenkichi Yabashi, its neoclassical design features a balanced façade, stone columns, and Western-style windows, reflecting Seoul’s early steps into modern institutional architecture.

101, Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul

9) Bumingwan

Completed in 1935 as a multi-purpose civic hall, Bumingwan was one of the most modern facilities of its time, with an 1,800-seat auditorium, smaller theaters, a restaurant, and even air-conditioning and heating. It quickly became a cultural hub, hosting theater performances, lectures, and film screenings. Later, the building was repurposed for propaganda and political gatherings, and after liberation, it briefly housed Korea’s National Assembly. Today, it serves as the Seoul Metropolitan Council, designated as a Registered Cultural Heritage, and stands as one of the city’s most significant colonial-era public buildings.

125 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul

10) Cheondogyo Central Temple

Completed in 1921 as the headquarters of Cheondogyo, this striking red-brick building stands out as one of Seoul’s rare examples of Vienna Secession style architecture. Designed by Nakamura Yoshihei, a Japanese colonial-era architect, with assistance from German designer Anton Feller, it combines bold geometric forms with Baroque flourishes in its front tower. Granite foundations and red-brick walls give it both solidity and elegance. Designated as Seoul Tangible Cultural Heritage No. 36, it was once counted among Gyeongseong’s “three great buildings” and remains an enduring symbol of cultural resilience.

11) Former Seoul City Hall

Built in 1925 during the Japanese occupation, the former City Hall is a prime example of Imperial Crown Style architecture with Renaissance influences. It served as the seat of city government until 2008 and today houses the Seoul Metropolitan Library.

Behind it rises the new Seoul City Hall, a large wave-like glass structure designed to resemble a giant tsunami. The form has been read as a metaphor for the “Korean Wave” rising over a Japanese-era building — echoing both Korea’s regained independence and the natural disasters that so often affect Japan.

Credit: Piotrus (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

110 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul

12) National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

Designed by architect Yoshihei Nakamura in 1938, the Western-style wing of Deoksugung Palace — once a residence of the Korean imperial family — originally functioned as a royal museum displaying the Yi family’s treasures. The building reflects both the luxury afforded to Korean nobility and the tensions of maintaining royal status under colonial pressure. Today, it forms part of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Deoksugung branch, where contemporary exhibitions unfold inside a space once tied to monarchy and empire.

99 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul

Bonus Entry) Akasaka Prince Classic House (Tokyo)

Built in 1930 as the Tokyo residence of the Korean Imperial Family, this two-story Tudor-style house with Gothic details was designed by Kozo Kitamura and Kaneyoshi Gondo of the Imperial Household Ministry. Set on the hill near the Akasaka Palace, surrounded by Japanese imperial and aristocratic mansions, it reflected the imperial family status granted to the Korean royals after annexation. One of the most expensive projects of its time, the Gothic Tudor house took four years to complete and combined an eclectic mix of influences: a Spanish colonial façade, medieval French roofline, and Jacobean interiors accented with Japanese motifs. Its craftsmanship included carved reliefs, stained glass, and hand-painted tiles.

After the war, the US occupation stripped both Japanese and Korean royals of their titles, apart from the immediate imperial household. The Yi family lost their status, and the residence was converted into the Akasaka Prince Hotel. In 2011 it was designated a Tokyo Tangible Cultural Property, restored, and reopened in 2016 as the Akasaka Prince Classic House, now a wedding and event venue.

Among its last residents was Yi Ku, son of Crown Prince Yi Un and Princess Masako of Nashimoto. He was the grandson of Emperor Gojong of Korea and second cousin to Japan’s Emperor Emeritus Akihito. Born in this house, Yi Ku later returned to Korea as an ordinary citizen after independence. In his final years, he came back to Tokyo as a guest at the hotel that had once been his home. He died there of a heart attack.

More Than Instagram Backdrops

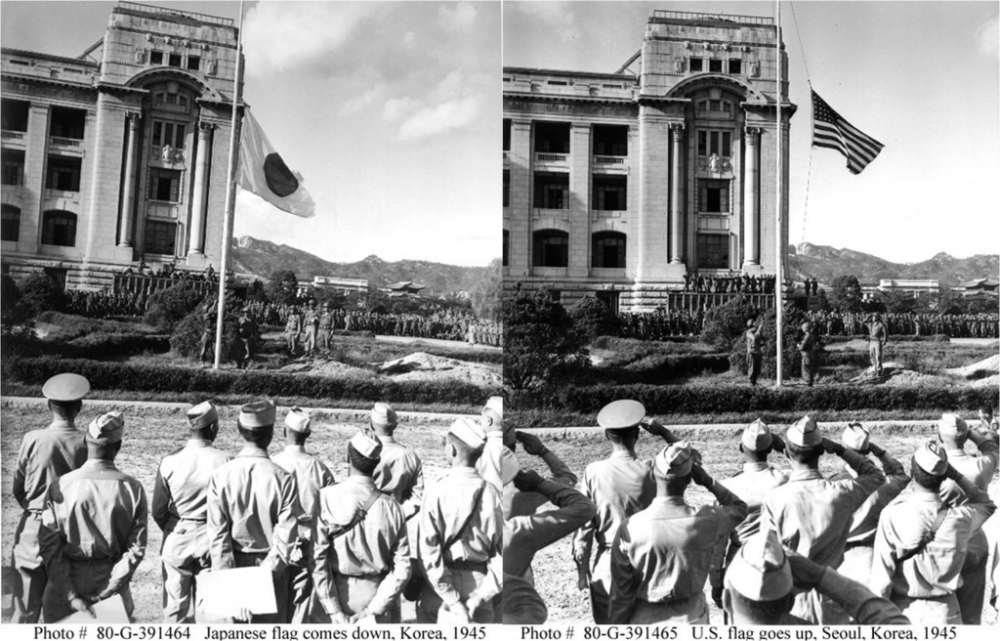

These buildings carry a complicated weight. They are reminders of a brutal colonial era, layered with memories of Japanese occupation. At the same time, they are rare tangible survivors — structures that endured through turmoil and change.

Think about it: they survived the colonial era, and when independence finally came in 1945, the peninsula was immediately caught under the competing imperialisms of the United States and the Soviet Union, leading into the devastation of the Korean War. Though many required restoration, these buildings remain tangible witnesses to the hardships the Korean peninsula faced in the 20th century.

Credit: The US Navy (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

Of course, like many architectural objects, we can appreciate their beauty, design, and the layered histories they carry. Buildings are not only façades but witnesses; they have seen, hosted, and shaped what people have done and thought. Many of us are still drawn to sites marked by darkness, whether ancient pyramids tied to authoritarian monarchies, large forts built on violence, or lavish palaces that symbolized wealth and the exploitation of citizens.

In Seoul, these structures echo styles found in surviving Japanese buildings, as well as colonial architecture in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and across the Pacific from Palau to Chuuk. Seeing those parallels allows us to trace an interconnected history of empire in Asia and the Pacific — and even beyond. They also reveal how Japan sought to position itself not as a victim but as a perpetrator of European-style colonialism by adopting the European architectural style.

Elsewhere, colonial architecture is often flattened into picturesque backdrops for Instagram. Portuguese façades in Macau or any British influence in Hong Kong are reduced to “European moments abroad,” promoted as aesthetic attractions or fun facts. Many tourism outlets advertise them as a kind of fun cultural fusion or even as a way to “visit Europe without leaving Asia.”

In Seoul, preservation carries a different intention. These buildings are not only cute Instagrammable spots but deliberate sites of memory, kept to confront history as much as to admire their lines. That choice itself offers a lesson, one that others could stand to learn.

Credit: unknown (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

Credit: USAG- Humphreys (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

Credit: unknown (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

Credit: unknown (Wikimedia Commons) / Public Domain

Read on:

The Diversity of Tokyo’s Architecture