August 5, 2021

City Girl in the Japanese Countryside

New Yorker settles in an unlikely place

“Karen! Hey! How’re you doing?”

“Fine, fine. And you? It’s been a long time.”

“You’re telling me. It’s been about fifteen years. But I’ve heard all about you.”

“Oh, really—what’ve you heard?”

“That you married a millionaire, have seven children, and live in China.”

“!!??!!”

In this telephone conversation with an old friend during a visit to the States, I had to set the record straight, on all counts.

“So, when are you coming back?” my friend wanted to know.

I used to hear that all the time. No one asks anymore.

Having lived here forty-six years, quite naturally, I call Japan home.

My husband and I, both New Yorkers, lived our first year in Japan in the city of Mishima. He had a one-year scholarship and when the year was up we decided we’d stay “a little longer” – we also decided to stay in Shizuoka prefecture. We wanted to raise our children in the countryside, and it doesn’t get more country than Futokoro Yama (Breast Pocket Mountain), the small village where we settled in the mountains north of the city of Hamamatsu. Our new home, at the very top of the mountain, came with a soul-enhancing view of bamboo groves, tea fields, endless sky, and air so clean and sharp we city people felt like we were breathing oxygen for the first time.

Our home, an old farmhouse with all tatami rooms, had neither beds nor chairs, and no conveniences (I’ll spell that out: no hot running water, no flushing toilet). We built a fire every night to heat the bath, kept warm in winter sitting at a sumi hori-kotatsu [kotatsu heated with charcoal]. When we settled in the farmhouse in 1976, although the area wasn’t as depopulated as it’s become, I could count my neighbors on two hands. Country living meant I had nothing that could be called a social life. Growing up in New York City, where party was an active verb, for the seven years we lived on Futokoro Yama, the only time I got to dance was when I put on a yukata [cotton kimono] to dance in the summer festival.

Our children went to the local school, and the walk home was one hour uphill. The school uniform required shorts be worn year round; they attended classes barefoot, and in hot weather their teachers held classes by the river. Summers for our kids weren’t just a time to hunt kabuto mushi [rhinoceros beetles] but to camp out in the neighborhood with friends (no adults) anywhere they pleased. They could identify, prepare, and cook such wild vegetables as warabi tsukushi, and yomogi [bracken, field horsetail, and mugwort].

Once, years ago when my youngest daughter was in elementary school, she was introduced as an American at an international event. When asked where she was from, she answered New York. At the time she’d never been to New York. I guess it was her way of being accommodating, since she told me, “They expected me to be from America.” So I instructed, “Next time you can say: I’m American. My parents are from New York. I was born in Hamamatsu, and I live in Tenryu.” She protested that was too long and complicated and confusing. I could only respond that sometimes the story is not so short and simple and that “People will just have to adjust their minds.”

And we too had to adjust our minds as we became fixtures in the community, and were required to play unsought roles. I was chosen to be vice-president of the kodomokai [children’s association], my husband served a term as head of the jichikai [neighborhood association].

We now live 20 minutes away from Breast Pocket Mountain. The rural residential development of single family homes where we’ve bought land and built our house, is not only the antithesis of metropolitan life, it’s a place that might best be described by what it doesn’t have: cafes, bookstores, lots of people. I once quipped that if three people walked up the road at the same time I would’ve thought it was a parade! “Order out” are two words I never get to say.

I still call myself a New Yorker though it’s not making much sense anymore. I haven’t lived in New York City for fifty years. When I visit, I don’t get lost (as sometimes happens in Tokyo) but familiar landmarks that would’ve guided me have disappeared. I no longer recognize neighborhoods where I could’ve told you where to find the best bagels or delicatessen; I can’t say where the best Salsa bands are playing.

This New Yorker now makes her home in Shizuoka prefecture, and area of Japan known for sticking to old customs and formalities. It’s a place where a plethora of rules, written and unwritten, and daily obligations, are adhered to. Though not necessarily said with pride, people here don’t hesitate to describe the prefecture as hoshuteki [conservative]. While I couldn’t have guessed that I would create a niche here and develop feelings of deep attachment, indeed I have become comfortable in a place that is easily the polar opposite of the place I come from.

And I’m still kind of surprised I could live in a place where people don’t dance at parties.

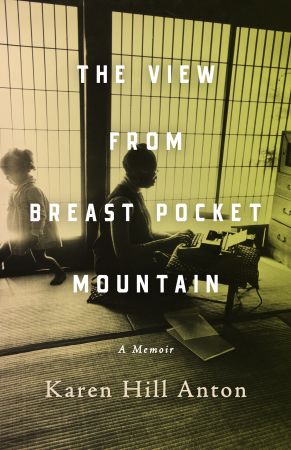

Karen Hill Anton is author of the award-winning memoir “The View From Breast Pocket Mountain.”

KarenHillAnton.com

Love literature about Japan? Also check out these other stories:

6 Japanese Mystery Novels to Read in 2021

Honkaku, thrillers and crime sagas — Japan’s got it all

Mieko Kawakami’s ‘Heaven’

One of the most anticipated Japanese novels of 2021

The Sacrifice Needed to Live Between Cultural Worlds

Liane Wakabayashi’s new memoir ‘The Wagamama Bride’