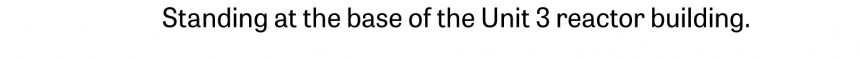

Our tour van came to a stop in the pass between the Unit 2 and 3 reactors. The gap, once consumed by radioactive rubble, had been cleared several months before our visit to the Fukushima Daiichi plant in June. “You’ll have 10 minutes outside before we move onto the next location,” our guide announced to the vehicle, a portable Geiger counter in hand. We buckled our construction helmets, tightened the strings of our face masks and stepped out onto the open road. The Pacific coast was no more than 200 meters in front of us and on either side were nuclear reactor buildings. While Unit 2 was weathered but structurally intact, Unit 3 showed visible scars from the explosion it had suffered seven years earlier, marked by protruding support beams and fractured cement walls.

Since our day began at the edge of the exclusion zone in Tomioka, Fukushima, we had passed through half a dozen security checkpoints and received a full-body scan to measure internal radiation, a baseline reading for later comparison. Now, at the power plant, facing the shells of two nuclear meltdowns, our observation time was further regulated to minimize exposure. A visit to this part of the plant came with the understanding that just steps away were structures housing melted nuclear debris, the epicenters of one of the largest nuclear disasters in history.

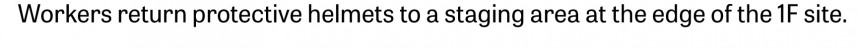

There were no hazmat suits or gas masks, the biohazard uniform most would imagine for this portion of the tour. Pants and a long-sleeved shirt was the required outfit, a protective layer augmented by gloves, a helmet and what could pass as a kafunsho (hay fever) mask. We were directed to tuck our pant legs into four layers of neon blue socks, which we slid into black ankle-cut rain boots. A personal Geiger counter was placed in the chest pocket of our mesh vests. It would set off an alarm when it reached the tour’s daily allowance for radiation exposure, 100 microsieverts, equivalent to a roundtrip flight between Narita and JFK. In our meticulously planned day-long tour, these counters wouldn’t reach more than 30 microsieverts.

The optics of this moment, standing in plain clothes next to two nuclear reactors, were not lost on Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which operates Fukushima Daiichi and facilitated Metropolis’ tour of the 3.5km² power station, known internally as 1F. Our guide remarked that they often bring visitors to this spot. Safely getting up close to one of the reactors, even if only for 10 minutes, is a gesture they hope will show conditions at the plant have improved substantially since the 2011 disaster.

In the past year, TEPCO has expanded the number of power station tours for journalists and the general public. These tours are an effort to increase transparency and educate the public on the plant’s status. They are also an effort to build goodwill for a company that is still maligned by many for its culpability in the disaster. Three retired TEPCO executives, Ichiro Takekuro, Sakae Muto and former chairman Tsunehisa Katsumata, are currently on trial for “professional negligence resulting in death and injury,” a criminal charge for ignoring internal reports that Fukushima Daiichi was at risk from a debilitating tsunami wave. The indictment was brought by a civilian judiciary panel, overruling prosecutors who had twice declined to press charges. The criminal trial follows a string of civil suits, including a ruling by a Tokyo court last year that ordered TEPCO to pay ¥11 billion (100 million USD) in damages to the residents of Minamisoma, Fukushima.

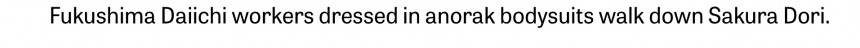

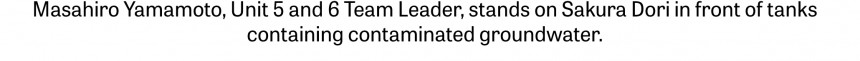

As part of these tours, TEPCO is promoting what they consider major improvements to working conditions on the plant. Currently, 96 percent of 1F can be accessed with the “regular uniform” we wore during our tour. One of the most advertised portions of the plant is Sakura Dori, a roadway at the edge of 1F that has been specially maintained in order to match regularly-occurring radiation levels in Tokyo. Before the disaster, families of plant workers and local residents would gather under the road’s 1,000 blooming cherry blossoms trees for hanami (cherry blossom viewing) every April. This past year TEPCO invited journalists to Sakura Dori for a photo-op of the 380 trees that remain.

These entwined motivations of public education and public relations valence any visit to 1F, including Metropolis’. But even a manufactured look behind the power plant fences provides insight into the personal and working lives of the 5,000 people who are employed at Fukushima Daiichi daily. Their roles are diverse, from nuclear engineers and security guards, to bureaucratic liaisons and cafeteria servers. Decontamination workers stand alongside janitorial staff. There is even a fully-stocked Lawson convenience store tucked away in an administrative building with cashiers working the registers. Each of these workers wakes up every morning and must pass into the Fukushima exclusion zone on their way to work. Some even enter reactor buildings, earning their livelihood by putting themselves in proximity to dangerous nuclear debris.

As we walked down Sakura Dori towards our tour van, we passed a couple dozen workers; some matched us in attire, others wore blue TEPCO-issued coveralls, others wore anorak body suits and full-face masks, used in the plant’s most radioactive areas, or “R zones.” It was a muggy summer afternoon with grey clouds forecasting heavy rain. We were told heat stroke is a common problem when wearing full-body protective gear, one motivation behind efforts to make 1F more accessible with regular clothes. Without fail, though, each worker shared a hearty “otsukaresama” as they passed one another. The greeting is used to offer thanks for hard work; its literal translation addresses “someone who is tired.” Unlike PR officers, TEPCO executives and Diet legislators based in Tokyo’s Chiyoda Ward, it is 1F’s decommissioning workers who must walk Sakura Dori every day — not just when the cherry blossoms are in bloom. In some form, they will likely be walking this road for decades.

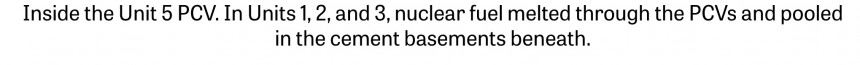

On March 11, 2011 at 3:27 pm, a tsunami wave 13 meters tall crested over the six-meter seawall of Fukushima Daiichi’s complex, flooding the grounds with a force that crippled the nuclear power station’s vital cooling systems. Without electricity required to pump water into the reactors, the waterline dropped below the core rods in Units 1, 2 and 3, instigating a nuclear meltdown in each. Inside these reactor walls, boiling pools of stagnant water produced volatile amounts of hydrogen gas (a Zirconium-steam reaction). Within days Units 1, 3 and 4 (connected to the Unit 3 building by pipes) had all suffered explosions, carrying nuclear fallout over the Pacific and inland, disseminating across the towns of eastern Fukushima Prefecture. The nuclear fuel in Units 1, 2 and 3 soon melted through their primary containment vessels (PCVs) and pooled in the cement basements of each respective building, where it remains to this day.

Masahiro Yamamoto, 42, was there on March 11. In fact, he’s been at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant for over 20 years, his first and only job since university. Born in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, where southernmost Honshu meets the tip of Kitakyushu, Yamamoto enrolled in a TEPCO-affiliated high school. Trained as an engineer, the feeder program placed him at the Fukushima plant back in 1994, where he worked a steady engineering job and raised his three children in Futaba. One of two towns that border 1F, the evacuated municipality currently has an actual population of zero.

“Before the disaster, I worked just like an average salaryman. But as disaster struck and the situation worsened, it was as if I was dropped right in the middle of a battlefield,” he says. We don’t dwell on this difficult time, but Yamamoto shares some fragmented memories. “The monitors for the reactors started to show signs of abnormality, and I thought to myself, ‘what is going to happen now,’” he remembers. “My family lived nearby and I wanted to check their safety, but I had no way of communicating with them so I didn’t know whether they were swept away by the tsunami or injured by the quake. I had many worries, but I had to bury my feelings and focus on my duties. I managed to control myself up to that point.”

The Self-Defense Force came first; then other government agencies arrived — “When I was walking down the aisle to go to the restroom, the Prime Minister passed right by me.” Yamamoto’s workplace in a quiet seaside town had overnight become ground zero for a Level 7 nuclear accident, matched in severity only by the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. He describes himself and his team as co-workers that were suddenly required to be soldiers faced with daily life-threatening work. “When Unit 1 exploded, I was wearing my mask to go outside and work onsite at the reactors. I felt [the blast] blow across my face. Things took a turn for the worse and every time we had to go near the reactor buildings, our team was assembled knowing that there may be an explosion and we might die. We had to go through that many times, and it was psychologically hard on me.”

Seven years later, the realities of working at Fukushima Daiichi have changed dramatically for Yamamoto. Along with 750 other TEPCO employees, he lives in company dormitory housing in the town of Okuma, just outside the exclusion zone. His family evacuated during the disaster and they have been living in Tokyo’s Otsuka neighborhood ever since. Long train rides on weekends are the only way he spends time with his wife and three children before returning to his duties at the plant.

“There’s nothing special about my job,” Yamamoto says, despite all signs to the contrary. “I think any work is hard and challenging.” He describes his average day, far removed from the emergency response. Early mornings begin with weight training; nights are spent studying eikaiwa (English conversation). He’s working to improve his English skills, in part, to share his experiences at the power plant and dispel fears about visiting Fukushima Prefecture. “I’d like many foreigners to come to Japan to learn not just about the fun things, but also about [Fukushima Daiichi] and the reality.”

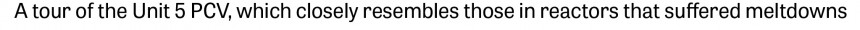

Yamamoto currently serves as Team Leader at Units 5 and 6, two reactors that were spared from nuclear meltdowns but are set for decommissioning. While important work, this is only one part of an elaborate operation that also aspires to full decommissioning of Units 1, 2, 3 and 4 by 2050. Now seven years into this proposed timeline, some critics have questioned its feasibility. According to Daisuke Hirose, a TEPCO spokesperson who debriefed Metropolis on the state of decommissioning, there are three major priorities in fulfilling the plan as scheduled.

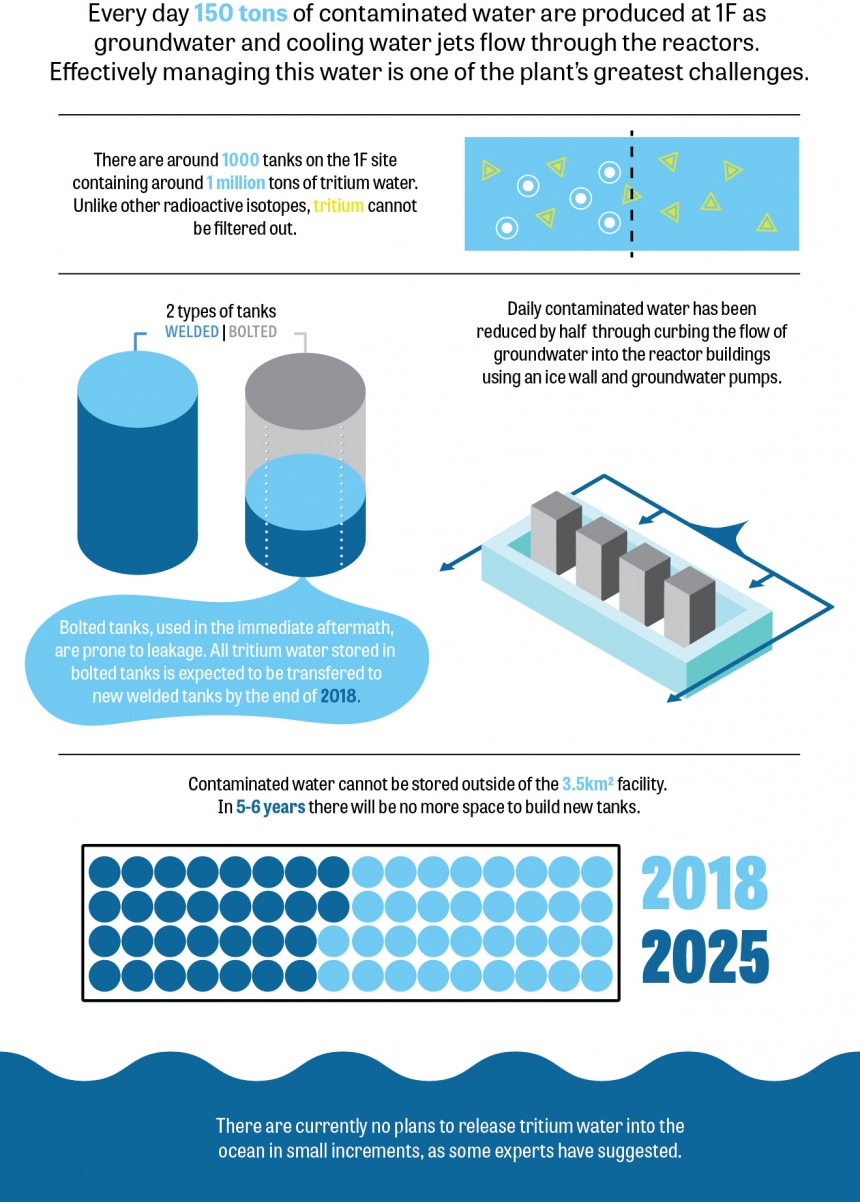

The most complex is the location and extraction of nuclear fuel debris. Hundreds of tons of melted fuel remain buried deep within Units 1, 2 and 3, the exact locations of which remain unknown. Rubble and fatal radioactivity levels have rendered these parts of the reactor buildings inaccessible to humans, leaving remote-controlled robots the most viable method of investigation. Only minimal fuel debris in Unit 2 has currently been identified and the means of extraction have not been finalized, but Hirose says TEPCO will meet a 2021 benchmark for initial fuel extraction. Alongside the handling of nuclear debris, the plant must confront a rapid accumulation of contaminated water on site, perhaps the most urgent task facing the operation.

Despite the pressing and complex problems facing the project, Hirose argues that improving the safety of the plant must rank above all other priorities, “Decommissioning is something done by people. Our most important task is improving conditions at 1F for decommissioning workers.” Yamamoto, for one, insists he does not worry about his health while working at the plant. “At the time of the disaster, I couldn’t comprehend all the issues about contamination and radiation exposure, so I was very worried back then,” he says. “I don’t have those worries now.” Yamamoto’s duties at Units 5 and 6 include routine exposure to radiation, but he does not currently conduct work in the plant’s most radioactive locations. While we requested to speak to an employee with work duties in the R zone, TEPCO declined the request citing the priority for these employees as decommissioning work. “Of course, to be honest, there are some people who’ve suffered health damage, as has been reported in newspapers, so it’s not a zero,” he adds. Currently, 17 employees at 1F who’ve developed cancer have applied to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare for compensation as a work-related illness. In September, the Ministry acknowledged the first death related to radiation exposure at 1F, a subcontractor in his 50s who died of lung cancer.

Once a meishi (business card) that held tremendous social capital, TEPCO is now a company irrecoverably associated with the disaster. To many, the workers of Fukushima Daiichi are the face of this institution. Yamamoto shares stories of coworkers’ doors being vandalized with graffiti and trash being dumped in front of their homes. It is difficult to find sympathy for the TEPCO workers at 1F when considering the continued injustices suffered by the residents of Fukushima, but the victims of the nuclear disaster and the rain boots on the ground at 1F are not necessarily distinct populations. Around 60 percent of the employees at Fukushima Daiichi are from Fukushima Prefecture, a number that TEPCO says may be underreported since it only includes those born in the prefecture. In many instances, including Yamamoto’s, the workers at 1F are working towards recovering their own communities in the entwined futures of decommissioning and Fukushima’s restoration.

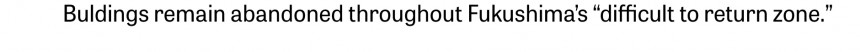

Our coach passed the border of the “difficult to return zone,” a government-designated boundary that separates areas of Fukushima deemed habitable from those deemed uninhabitable. Suddenly we were facing the Fukushima “ghost towns” of popular imagination. While Fukushima Daiichi is ground zero, the heart of this disaster is in the abandoned towns of the prefecture: homes and businesses and schools left behind in an instant, hard evidence of the 160,000 residents that were displaced by the disaster. Abandoned vehicles, shattered windows, hollowed-out storefronts, a dilapidated pachinko parlor and seven years of weeds rising from cracks in the cement — they all passed by the coach windows on our approach to Fukushima Daiichi.

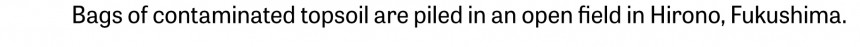

We were not the only vehicles on this highway, trucks rumbled past us and cars lined the road. Calling these “ghost towns” is a misnomer: these towns may be uninhabited, but they are not unoccupied. Many of these vehicles belonged to a decontamination project that spans the original 20km exclusion zone and beyond. It is not operated by TEPCO, but rather a web of government agencies and municipalities. Their job, first and foremost, entails the mass removal of dirt, stripping entire towns of topsoil and manually washing down rooftops and other surfaces that were doused in radioactive particles in an effort to clean away radiation. Fields of black refuse sacks, millions of which are filled with contaminated soil, now litter the prefecture without plans for their permanent storage or removal. Regardless of this work’s efficacy, it is an undertaking that requires a massive labor force; Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reports that more than 46,000 were employed in Fukushima decontamination work in 2016.

The harsh reality is that the disaster has disrupted the industries that once thrived in Fukushima Prefecture — fishing, agriculture and service jobs. Currently, only half of the region’s 1,000 fishermen are going out to sea and they face highly reduced demand. The decontamination industry is one of the few thriving seven years later, but this line of work is not without its risks. In early September, the UN human rights division released a statement warning of possible worker exploitation in the recovery effort, both within the prefectural decontamination projects and on the 1F site. “Workers hired to decontaminate Fukushima reportedly include migrant workers, asylum seekers and people who are homeless,” wrote three UN Special Rapporteurs. “They are often exposed to a myriad of human rights abuses, forced to make the abhorrent choice between their health and income, and their plight is invisible to most consumers and policymakers with the power to change it.” Japan’s Foreign Ministry responded by calling the statement “extremely regrettable.”

We met Yamamoto in the parking lot of the plant after our tour. His TEPCO uniform had been exchanged for pants and a graphic-T. It is the second time we’d met that he had worn this particular gray short-sleeved shirt with a Ghostbusters logo emblazoned on its chest, one of his favorite movies as a child. Outside the plant, Yamamoto sheds his professional facade to reveal a youthful energy. During the night ahead we would visit an izakaya (Japanese pub) in Iwaki City and share stories over local sake and sashimi (sliced raw fish), once celebrated Fukushima products that have since been cast off supermarket shelves as new associations and stigmas took hold of the prefectural name.

There are many people who shoulder the burden of the nuclear disaster: parents sending their children to school with Geiger counters on their backpacks, farmers who have lost their livestock and livelihood, elderly left to care for deserted towns as the young set roots far from Futaba-gun, multi-generation Fukushima lineages that have been forced to abandon their familial homes for prefabricated temporary housing units. Yamamoto carries one small burden of this sweeping tragedy, as do the other workers of Fukushima Daiichi, as do those who labor in irradiated fields without other means of income. They are trying to extinguish a danger that can’t be seen, but its presence is felt in every aspect of their work. At times the job they’ve been assigned feels beyond comprehension, but Fukushima is not a supernatural disaster and Yamamoto is no ghostbuster. This disaster is deeply human, founded in both nature and negligence. “If you think in terms of decades, the long road ahead and the abstractness of it all will crush you,” says Yamamoto. “But just as with any other work, if you split up big projects into smaller pieces, the feeling of accomplishment from each small victory will keep you motivated.” Inside the exclusion zone, we witness the people of Fukushima trying to take their land a few steps closer to normal.