April 30, 2017

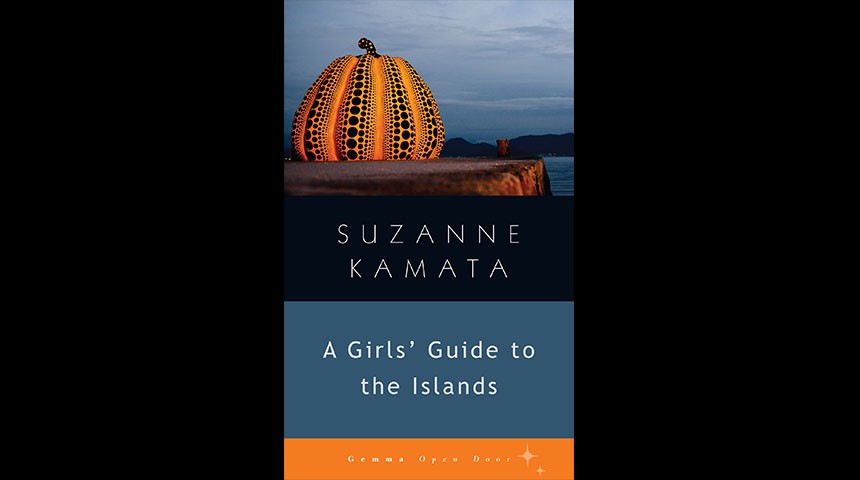

A Girl’s Guide to the Islands: Not Your Typical Travelogue

A mother-daughter travelogue, which tugs at the heartstrings

By Joan Bailey

Books and travel provide a window to other worlds and other lives. We take up both in an effort to enjoy ourselves and learn by turns. At first glance then, A Girl’s Guide to the Islands by Suzanne Kamata appears to be a mother-daughter travelogue, introducing the adventure of a new place whilst tugging at the heartstrings, bringing a tear to the eye and throwing in a few laughs here and there. While A Girl’s Guide certainly accomplishes all of this, Kamata also manages a bit of the unexpected.

As a prolific author of young adult novels, this is Kamata’s first work of young adult non-fiction. However, she brings her storytelling skills to bear on a series of trips she took to Japan’s Seto Inland sea with Lilia, her artistically inclined and multiply disabled daughter. Accessible often only by ferry, the islands depicted here have transformed themselves in recent years into self-described “Art Islands.” Giant sculptures and ornate museums are set against the stunning backdrop of stark cliffs and traditional fishing villages in the vastness of the Inland Sea.

The book begins, however, not on an island but with Kamata pondering how she might rescind an invitation she made to her then twelve-year-old daughter to visit an art exhibit in Osaka. Yayoi Kusama, a Japanese artist Lilia adores, has a show at a museum there. In a burst of enthusiasm, Kamata suggested the trip but is now unsure that she’s up to going. It’s a long bus ride. She worries her daughter will get bored on the way. She’s worried about maneuvering Lilia’s wheelchair alone. Kamata feels tired just thinking about it; however, Lilia, wants to go.

The Osaka trip, of course, turns out to be a success. Mother and daughter both enjoy themselves and the show, so much so that Kamata is inspired to suggest another trip. She proposes an overnight journey a bit further afield to one of the Art Islands.

Kamata, an American raising her family in Japan, is a knowledgeable and thoughtful tour guide, providing plenty of interesting details and vignettes about the places she and Lilia experience. No less compelling, though, is the fact that her daughter is deaf and has cerebral palsy. Traveling with a wheelchair means navigating Japan’s surprisingly inhospitable terrain for the disabled. There are no elevators to the upper deck on the ferries, so she and Lilia simply wait in the car. More than once as they take in an exhibit, Kamata writes “There was no ramp.” Lilia sometimes sends her mother on without her, and sometimes the two simply skip viewing a piece altogether.

Similarly, Kamata does not paint her relationship with her daughter in a special or rosy light. They are, after all, a mother and pre-teen daughter. There are battles over Wi-Fi, iPad’s, and going out. There is teen laziness, motherly nagging and plenty of eye rolls on both sides. Yet Kamata also allows readers inside her hopes and dreams for Lilia, the same as any parent anywhere in the world. She is often frustrated by the limits that others put on her child because of her disability.

Readers also meet in Lilia a typical young woman eager to explore the world and test her abilities. We watch as she begins to develop a critical eye for the art she sees and we listen as she reflects on these new experiences. It is at times startling to be reminded that Lilia speaks in sign language and maneuvers in a wheelchair, which is, of course, a primary point of the story.

Like any good travelogue, readers take in the scenery, culture, and cuisine through the writer’s eyes. We share their meals, hotel stays and wanderings about the islands in search of art. We get lost, find our way, and are charmed by the people we meet. Kamata effectively brings the islands and art to life, and as we get to know mother and daughter better, we find them both insightful and humorous travel companions.

The result is a young adult book which beautifully captures the unique scenery and special features of each place Kamata and her daughter visit. But also one which vividly portrays life in Japan with a disabled child. Kamata challenges assumptions about disabled people and the obstacles they face with everything from the restroom to the art gallery. By the end of A Girl’s Guide to the Islands, readers find themselves back home again, full of memories from an unforgettable journey.

(full disclosure: Suzanne Kamata has written for Metropolis as freelance contributor)