November 22, 2022

Antcicada’s Cricket Ramen in Tokyo

Would you try the world’s first bug-based ramen?

By Rika Hoffman

Every summer, announced by the shrill shrieks of cicadas, Japanese schoolchildren emerge, nets in hand, to take part in the pastime of bug hunting. Of course, it’s more of an academic study (a catch-and-release situation—if the insect is lucky) than a culinary expedition. But these days, with the growing interest in sustainable, insect-based cuisine, bug “hunting” takes on new meaning.

It’s nothing new per se; Japan has a history of consuming insects. Inago no tsukudani, rice grasshoppers glazed in a sweet soy sauce mixture, was a common snack just a couple of generations ago.

Now the trend toward sustainability has seen bugs making a comeback, from Muji’s insect snack packs to fine dining insect cuisine, like the type pioneered by the Tokyo restaurant, Antcicada.

Offering both an insect-centric tasting course and a visually tamer cricket ramen, Antcicada opened in 2020 with the aim to provide an eating experience that will “broaden your perspectives and values.” Made with 160 domestic crickets disguised in the form of an innocuous golden broth, Antcicada’s cricket ramen is the gateway to more adventurous eats.

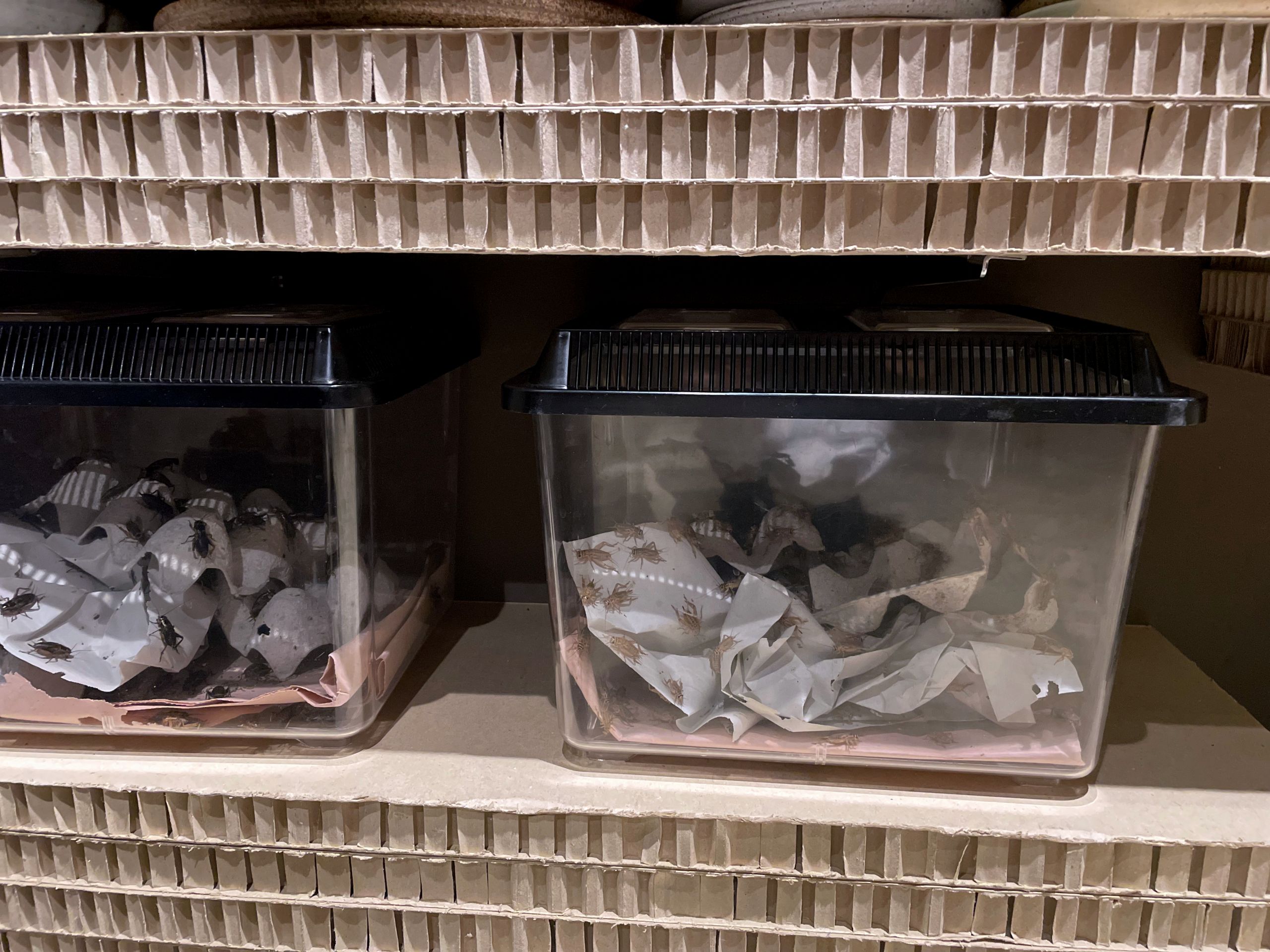

Inside the restaurant sit shelves of glass jars at varying stages of fermentation, with curious labels like “silkworm cocoon sauce” and some—even curiouser—unlabelled, with obscure contents. On another lower shelf are two plastic tanks of live crickets—one of which was spotted making a run for it, thwarting its fate of being made into a crunchy topping.

Cricket Ramen

With a golden-brown broth, pink slices of meat, and well-grilled menma, you wouldn’t know this ramen was anything out of the ordinary if it weren’t for the garnish: a large, fried cricket. Flavor-wise, too, it could easily be mistaken for a seafood ramen–like shrimp or niboshi; bright-tasting, with a slight yuzu fragrance.

Living up to its name, every component of Antcicada’s cricket ramen features the insect, from the dashi broth to the soy sauce base, and even the noodles, which are flecked with specks of powdered Futahoshi crickets from Tokushima. A blend of two types of crickets are used for the broth—Futahoshi crickets and European crickets—about 160 crickets per bowl, according to Antcicada’s staff, who brought out a hefty aluminum bowl of the spent dashi ingredients (92% crickets and 8% shiitake and kombu, in case you were wondering).

With so many “invisible” ingredients worked into the different components of the dish, Antcicada’s cricket ramen is a palatable and accessible entrypoint to the world of insect cuisine. Perhaps the most challenging part would be the fried cricket topping, which diners—if they can get past its appearance—will find has a crispy texture and nutty flavor.

Silk Sausage

While cricket ramen might be what Antcicada is known for, the rest of their à la carte menu is more experimental, featuring items like cricket beer and tsukudani. They swap out items every now and again, which I found out on my last visit when, to my dismay, the tagame (giant water bug) choco brownie I’d been keen to try was no longer on the menu.

The silk sausage was among the most intriguing on the menu, and came out from the kitchen smelling astonishingly like cordon bleu–and tasting like it too. The texture was akin to a fish ball, but less bouncy and more crumbly.

Kaiko no Funcha (Insect Dung Tea)

This one might be hard to wrap your head around: a type of tea made from the dried poop of moth larvae. Originating as an accident—a Chinese legend says moths broke into and devoured a supply of tea leaves, leaving only droppings behind—this tea supposedly aids in digestive health.

Antcicada’s kaiko no funcha tasting set came with two types of chilled tea: one from a Chinese kaiko and another from a breed in Yamanashi prefecture. The staff brought out tupperware of the droppings for us to sniff and, no unpleasant odors detected, we proceeded to sip the tea. The Chinese kaiko no funcha had a strong flavor, similar to rooibos tea, and a lingering aftertaste, while the Yamanashi variety was quite mild and smooth; both had an unexpectedly sweet fragrance.

Both times I’ve dined at Antcicada I’ve been impressed by its efforts to educate, and how it leads with genuine transparency. While it’d be easy to play up the shock factor of insect cuisine, doing so would not be a step towards normalizing this sustainable alternative to meat.

Antcicada is a safe space where diners can nurture new associations with “challenging” textures and flavors, observing our own preconceived biases about eating insects. Its open kitchen concept and the show-and-tell of ingredients from its staff bolsters the sense of transparency at Antcicada, taking the fear and discomfort out of an experience that might be the first for many, in the hopes that it might be the first of many.