March 3, 2026

How To Do a Hanami Picnic

A modern checklist for ancient celebrations

By Jessica Thompson and Arden Kreuzer

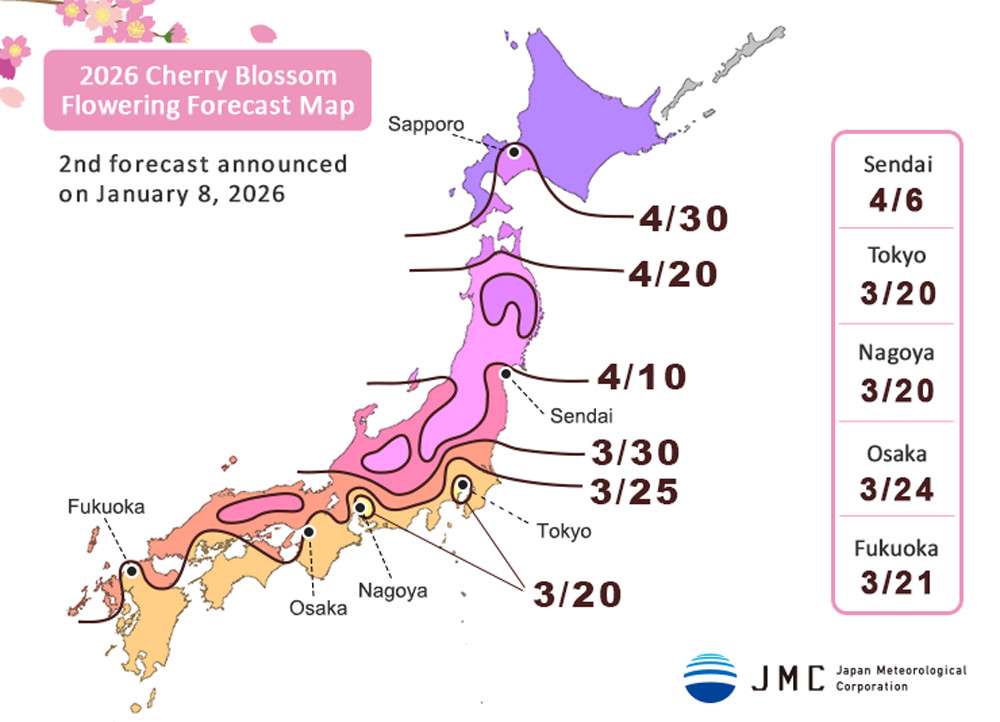

Each spring, Japan tracks the northward bloom of cherry trees with almost sports-like intensity. The official sakura zensen (cherry blossom front) begins in Okinawa as early as January and reaches Hokkaido by May, setting off weeks of hanami (cherry blossom viewing) picnics across the country.

Hanami isn’t just about pretty photos. It dates back more than 1,000 years, when farmers viewed the blossoms as a signal to plant rice and held feasts beneath the trees to pray for a good harvest. Today’s version swaps rice rituals for convenience store bento and canned beer, but the impulse is the same: gather, eat and mark the season before the petals fall.

Don’t miss the best things happening in Tokyo this week

A Brief History of Hanami

The first flowers to be the object of blossom-specific appreciation festivities, though, were actually ume (plum) blossoms. The trees were introduced from China during the Nara Period, a time when the Chinese Tang Dynasty had a profound influence on Japanese culture and lifestyle.

By the early Heian Era, cultural tastes shifted toward native sakura, and in 812 Emperor Saga hosted what’s often considered the prototype of modern hanami: poetry, music and sake beneath blooming trees. Annual celebrations ensued, but were still limited to Kyoto-based garden parties of the nobility.

By the late 1500s, warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi was throwing five-day hanami feasts in Yoshino, Nara, reportedly hosting 5,000 guests. During the Edo period, Tokugawa Yoshimune planted cherry trees in public spaces in Edo, opening the tradition to commoners.

Hanami became a popular spring excursion, and involved food, alcohol and tea enjoyed on mats laid under the fluffy floral canopies. The documented bento boxes of the wealthier attendees of the time included items like takuan (pickled daikon), flounder sashimi, sea bream, steamed white rice and chestnut paste.

Choosing Your Hanami Spot (and Getting There Early)

If you’re eyeing popular parks such as Ueno Park, Yoyogi Park or the Meguro River, plan to arrive early, especially on weekends. Groups often send one person in the morning to lay down a mat and “reserve” space.

A blue plastic tarp, known as a “leisure sheet,” is the unofficial uniform of hanami season. Write your group’s name on a piece of paper and tape it down if you’re claiming space for later arrivals.

Pro tip: shoes come off once you’re on the mat. Think of it as a temporary living room under a tree.

Here’s our list of the best spots to view cherry blossoms in Tokyo

Hanami Picnic Checklist

Most items are easy to find at convenience stores, supermarkets, Daiso, Seria, Tokyu Hands and Don Quijote during sakura season.

Drinks (It’s Basically a Nomikai)

Historically, hanami doubled as a nomikai (drinking party), and that energy hasn’t disappeared. Alongside sake, expect beer, chu-hai, sparkling wine and nonalcoholic options like sakura tea or seasonal soft drinks. Bring water too. Future you will be grateful.

Nowadays, hanamizake can refer more broadly to any alcohol consumed during hanami, from canned beer to nihonshu. Convenience stores and supermarkets typically stock limited-edition sakura-themed drinks each spring, including pink cans from Asahi, Sakura Beer by Sapporo, cherry-flavored chu-hai from Suntory and seasonal releases like Kizakura Brewery’s Sakura Nigori.

Hanami-zake or Sakura-zake (Cherry Blossom Sake)

Traditionally, this refers to a small cup of sake with a salted sakura blossom floating inside. Sake is easy to find at supermarkets and convenience stores and if you’re adding blossoms, use ones that have naturally fallen, never picked from the tree.

Hanami Bento

A hanami bento is less a specific recipe and more a context: food eaten under cherry blossoms. Typical items include grilled fish, tamagoyaki, croquettes, simmered vegetables and rice.

If cooking isn’t in your plans, convenience stores and supermarkets release seasonal sakura-themed bento each spring. Department stores offer more elaborate options.

For recipe ideas, see our guide to the best hanami bento recipes.

Shareable Finger Food

Think communal. Karaage, edamame, inarizushi, sushi rolls, cut fruit and sakura-tinted onigiri are reliable choices.

Some parks allow portable barbecues, but always check official park rules beforehand. Open flames are strictly prohibited in many central Tokyo parks.

Sanshoku Dango and Sakura Mochi

These have been a part of hanami picnics for hundreds of years. Sanshoku (tri-color) dango are skewers of pink, white and green sweet rice dumplings—pink for spring’s cherry blossoms, white for the winter’s snow, and green for summer’s yomogi (mugwort)—representing the seasonal transition. Sakura mochi feature pink-tinged rice wrapped in a pickled sakura leaf.

A Leisure Sheet (and Maybe Cushions)

Depending on the weather and your sensibilities, you can acquire a fabric rug, bamboo mat and, if you like a little extra padding, a zabuton (cushion) from homewares stores. Otherwise, a plastic tarp (usually blue) known as a “leisure sheet” is more widely available. Some bring low foldable tables and small chairs, easily attainable on Amazon or Tokyu Hands.

Zabuton on Amazon.jp

Leisure sheet on Amazon.jp

Low table on Amazon.jp

Small chair on Amazon.jp

Cups, Plates and Chopsticks

To keep things civilized. If you’re preparing ahead of time, environmentally-conscious options are available online for very reasonable prices.

Trash Bags (Nonnegotiable)

Public trash cans overflow quickly during peak bloom. Bring enough bags to separate bottles, cans and burnables. Taking your garbage home is standard etiquette. Hanami may look carefree, but it runs on quiet social discipline.

Staying Warm

Although hanami is a spring activity, the weather can still be chilly, particularly if you’re planning on yozakura (night blossom viewing), so best to bring along blankets, scarves or hand warmers.

Optional but Practical: Liver Tonics

Future-proof yourself with water and a bottle of Hepalyse or Ukon no Chikara, two commonly available liver tonics. Hepalyse is a blend of turmeric and—literally—liver; Ukon no Chikara is just turmeric. Drink one ideally before frivolities commence, but otherwise during or after.

Hanami Etiquette to Know

1. Don’t shake branches or pick blossoms.

2. Keep noise reasonable, especially after sunset.

3. Respect reserved spaces.

4. Leave the area cleaner than you found it.

Cherry blossoms last about one week at peak bloom. The short window is part of the appeal. Lay down a tarp, share food, look up once in a while, the petals will handle the rest.