February 7, 2018

Keshiki – New Voices from Japan

New book series showcases literary translation as cultural exchange (Part 2)

Part 2 – The Writers

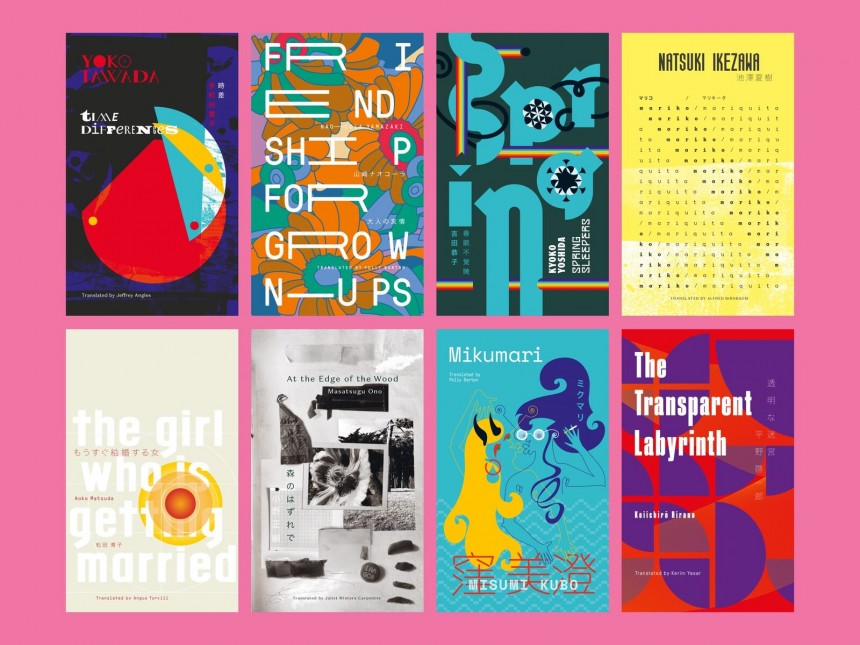

Keshiki – New Voices from Japan is a series of eight chapbooks by Japanese writers published by Strangers Press, a British publisher who believe that literary translation is a form of cultural exchange. In part one, Metropolis interviewed the translators behind the project. In part two, Clara Kumagai talks to the writers.

Masatsugu Ono is a Japanese author and translator who has won both the Akutagawa Prize and Yukio Mishima Prize. In his story for Keshiki, “At the Edge of the Wood”, a father and son wait together when the mother goes to her family’s home to have their second child. They live at the edge of a wood that holds strange sounds and beings within it and the story is uncanny and secretive, invoking images folk tales and getting lost in the forest.

CK: The woods have always occupied a deep part of the human consciousness, and that’s often captured in stories like the Grimm’s. In this story, there are mysterious old women and dwarves—were you inspired by fairy tales?

The woods which occupy a deep part of the human’s consciousness can be in this sense the human unconsciousness itself. It is possible that I was unconsciously influenced by the European fairy tales. Living in Orleans, France when I was writing this story, I think I was rather inspired by the real European woods, which seems to me completely different from Japanese mountainous woods.

CK: There are many unexplainable noises: coughing, whispering, rustling. Do you find yourself creating this aural element purposefully or is it always a part of your writing?

In the woods, even when we cannot hear anything, we can feel that the silence is full of the whispers of all the things there—sunlight, winds, water, green leaves, dead leaves, branches, birds and animals, spiritual and mysterious presences. Some voices are addressed to us, even though we cannot understand them. Trying to describe the woods, I could not ignore this aural element, i.e. the voiceless whispers of both visible and invisible things in the woods. I find this aural element is always a part of my writing.

CK: Even though place is so essential, it’s more psychic than physical—we are never told exactly where the characters are. Do you think there are landscapes that transcend their locations?

In this story, the place where the characters live at the edge of the woods must be anonymous and ambiguous. The name of place (the toponym) has strong connotations. It determines more or less how to read the story, giving concrete images connected to the real place to which it refers. For this story, I think the ambiguous landscape makes it possible to create a kind of psychological space, a margin out of which float the uncanny and intimate atmosphere.

Kyoko Yoshida is the only writer of the Keshiki series that required no translator. It’s not only that Yoshida writes in both Japanese and English—she translates experimental Japanese poetry into English and contemporary American fiction into Japanese. In “Spring Sleepers”, a young man has been diagnosed with ‘true’ insomnia, which doesn’t result in exhaustion from lack of sleep but rather the loss of memory and then of language itself. The style and the story had hints of Kafka and Beckett, but also its own delicate and surreal touch.

CK: You write of yourself as a “travelling theologian” (a wonderful title) and say that as a roving writer that can speak several languages, sometimes you have to make your “mother tongue strange.” How do you do this?

There are many ways to do this—as you yourself must have experienced as a journalist operating between languages and cultures—traveling, reading, writing in languages that you are not quite secure in, etc.…. For me, in the beginning, it was to write in my second language (English). After several years of writing fiction in English, I’ve realized that the way I write in Japanese has changed. As much as in English, operating in my own native tongue has become treacherous, or I have become aware that automatic speech or writing does not necessarily mean fluency or eloquence. Rather, words, when they surface automatically, reflect all sorts of faulty aspects—personal and cultural—which call to be re-examined, controlled and even sometimes admired.

Another important way for me to keep my relationship with languages “strange” is to translate. I translate both ways—into and from Japanese. I’ve translated American fiction into Japanese and Japanese experimental poetry and drama into English. To translate from your first language is against the norm. It’s an experiment because we all know we cannot reproduce the original in translation of verse. So it’s a failure from the beginning. I also like to think the author of the original text as an accomplice of my literary crime.

CK: Are there stories or characters that you ever feel like demand being told in one language or another?

It’s a wonderful question. I have several bestiary tales and when I write them, I wish for some kind of alien code language that I could use to capture their nonverbal existence. Since I am not capable of using or creating such code, I write in English.

When I write human characters, I realize I am not a ventriloquist type of writer. That’s partly because I write in a second language. Also, my stories aren’t very realistic. Sometimes I have no idea which language my characters are speaking in. I feel they are trapped in a foreign tongue whether the language is original or translated.