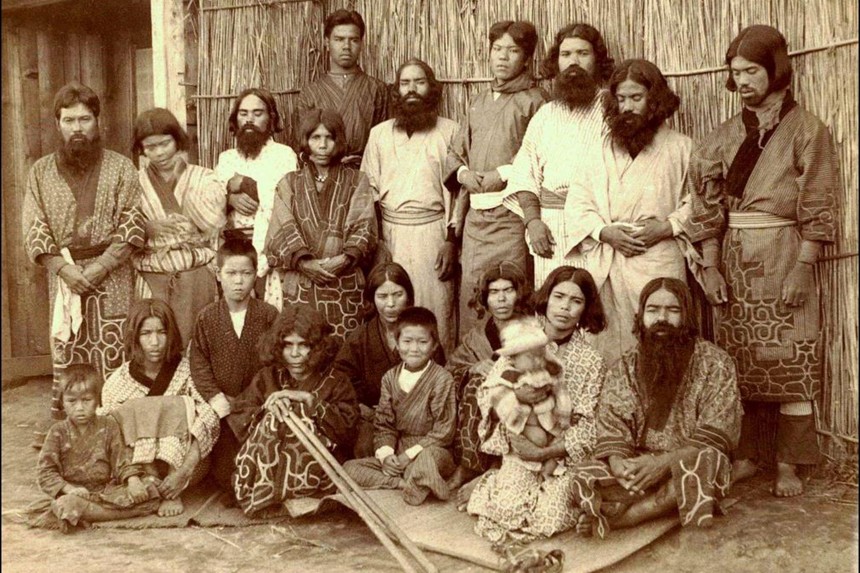

In February, a Japanese government spokesman said, “Today we made a Cabinet decision on a bill to proceed with policies to preserve the Ainu people’s pride.” The bill in question recognized the Ainu as indigenous for the first time, contrary to a centuries-old penchant for assimilation. But activists point out that the bill doesn’t grant self-determination or fishing rights; the government didn’t anticipate all the socioeconomic disparities, the echoes of its systemic racism.

Pride, stemming from perceived difference, is the culprit behind Japan’s tumultuous race relations. Racism here is wide-ranging, from internal ethnic tensions to anti-blackness to xenophobia, but at its heart is the idea of a single and uniform racial identity.

However, today the meaning of Nihonjin (Japanese) is increasingly hazy. It becomes so as Japan addresses, not without reluctance, its history of colonialism and present prejudices, which go hand in hand with the homogeneity narrative. But even today there are those who resist the multiethnic historic narrative of Japan.

Shin-Okubo is home to a large population of Zainichi (Koreans who came to Japan, forcibly or voluntarily, after the colonization of Korea). In 2013, there were anti-Korean demonstrations in Shin-Okubo, met by counter-protests. But organized pro-Korean action only arises in response to such flagrant displays, like when a former member of an anti-Zainichi civic group was indicted for hate speech last year. With all the nationalistic comments and message boards on the web — people lamenting the Japanese government’s supposed laxity towards “foreigners” — public racism is the tip of the iceberg. It seems that nothing beyond that is addressed by organized anti-racist movement.

Similarly there’s crucial discussion about anti-blackness only in the throes of controversy: take the nasty responses to Ariana Miyamoto’s selection as Miss Universe Japan, or the comic Masatoshi Hamada’s appearing in blackface on TV. Even the current administration seems blind to its own racism: Tomomi Inada, appointed defense minister in 2016, accepted donations from the aforementioned anti-Korean group. A recent hate speech bill hasn’t stopped any of the vitriol online, and is criticized as lacking teeth — it doesn’t actually ban hate speech. And of course, infamously, foreigners have legally been refused housing, services and government jobs.

This isn’t to say every foreign national in Japan is horribly mistreated. A lot of expatriates, immigrants and their descendants would probably testify to their positive experiences here, especially during one-on-one interactions with locals — race relations on the micro level. However, Nihonjin remains a phrase saturated with meaning; it denotes certain behaviors and even an appearance. As long as its definition remains so absolute, as long as a definition exists, people won’t acknowledge that the country is multiethnic despite the demographic reality. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy; systems will act to preserve the homogeneity narrative as long as they believe it. One harrowing consequence of this mindset is that less than one percent of asylum seekers are let into Japan annually. It’s easy to ignore this kind of “macro” racism because it may not affect everyone’s everyday experiences, but national pride is top-down, with certain policies and media portrayals coming to hurt those not deemed Nihonjin.