July 28, 2020

Talking With the Only Gaijin in the Village

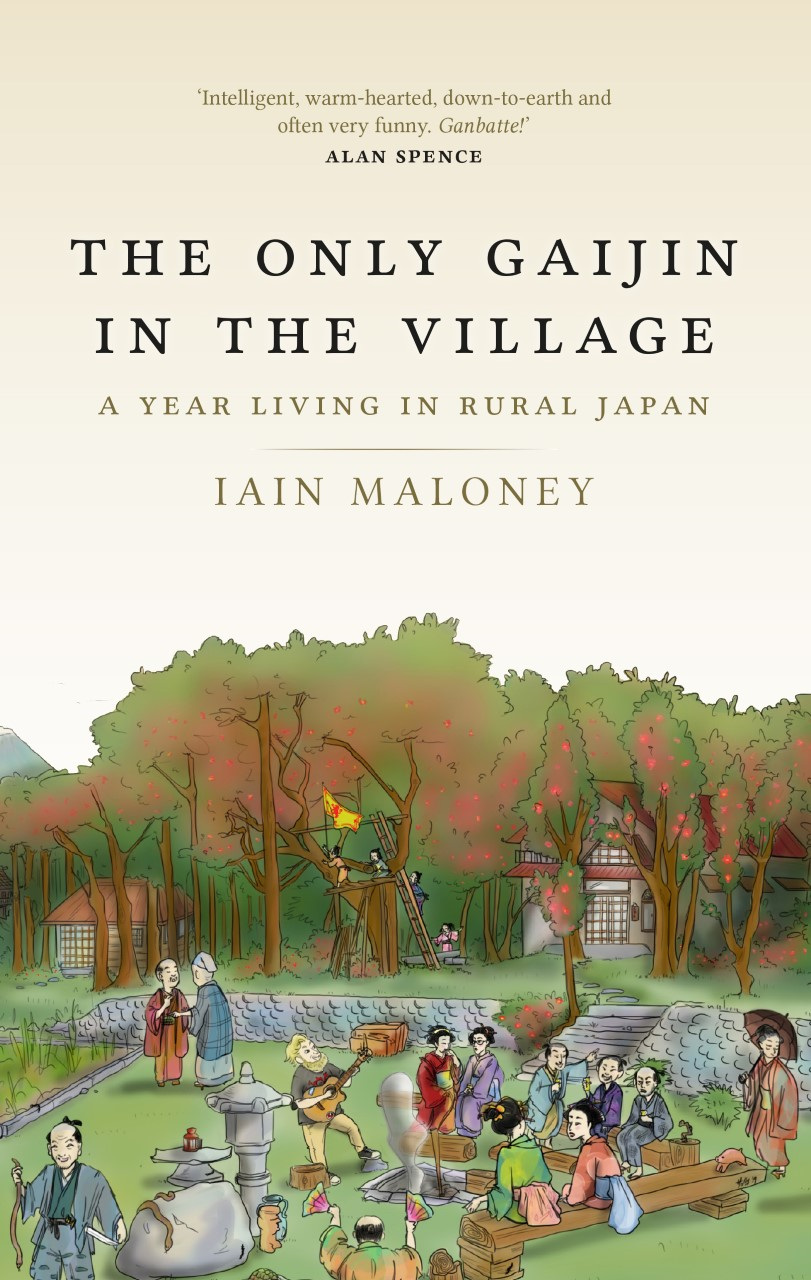

Scotsman Iain Maloney on his new book about life in rural Japan

By Paul McInnes

Aberdonian author Iain Maloney spoke with Metropolis about his latest book, “The Only Gaijin in the Village: A Year Living in Rural Japan,” which was published in March, 2020 by Polygon. Maloney, author of four other titles, has spent the last 15 years in Japan and four in his adopted village in the countryside and describes life in “The Only Gaijin in the Village” with his wife Minori and his relationship with his adopted homeland with humor, empathy and insight.

Metropolis: Where did the idea come from to write “The Only Gaijin in the Village?” What influenced you?

Iain Maloney: It started from a failed novel, funnily enough. I wrote a weird magical realist novel that I hoped would be my fifth book, but it didn’t really work and in the aftermath of that disappointment I felt I wanted to do something different. I started the “Only Gaijin” columns [on GaijinPot] as a way to explore a new style of writing [for me] and new subject matter. Memoir is very different from fiction, and I wanted that challenge. I also wanted to see if I could write comedy — the book is a mix of the comic and the serious but the original columns were just straight up comedy.

M: The chapter headlines are song titles from bands such as Mudhoney, Nirvana, R.E.M. and Mogwai. What was the thinking behind this?

IM: It started, as many things in this book did, as a way to amuse myself during the writing process. It started with the Mogwai titles — “Yes! I am a Long Way From Home” and “A Cheery Wave From Stranded Youngsters,” they so perfectly summed up the feeling I had when I moved to Japan. Music is a huge part of my life and these are all bands I listen to as I write, so in my mind there was always a strong link between the two. I fully expected my editor to tell me to change them but it turns out she’s a huge fan of many of the same bands, so they stayed. I made Spotify playlists of all the titles, so the book even has a kind of soundtrack.

M: You write about fitting in and assimilation in the book. Many foreign residents complain that they will always be seen as outsiders no matter how long they live in Japan. You seem to debunk this in the book. Can you expand on this?

IM: I’m over 6 feet tall, blond, with a bushy beard and the body of a retired rugby player — I’m going to stand out regardless of how good I get at the language, or how many customs I observe, so there’s no point pretending otherwise. My wife is Japanese but she’s also an outsider in this village — it isn’t a foreigner thing, it’s just the simple difference between being born and growing up somewhere, and moving there. If I moved to a small village on the west coast of Scotland I’d be an outsider there too, but so what? Standing out isn’t necessarily a bad thing. What’s important is how you are treated and how you treat other people. In the village I don’t have the same place in the community as my neighbor, who was born here, but neither does my wife, neither does the Japanese family who moved in down the street after us. We’re treated well, made to feel welcome — that’s the important part. We’re part of the community, we just occupy our own niche.

I don’t use the term ‘expat’ at all. It’s often used — sometimes unconsciously, sometimes deliberately — to mark a difference between different kinds of immigrants.

M: How has Japan and your relationship with it changed since you first arrived in 2005?

IM: It’s hard to say because I came here at 24 and I’ll be 40 this year, so I’ve changed massively in that time. This is my home now — as I say in the book, I plan to die here — so I feel much more comfortable than I did 15 years ago, but that’s to be expected as I’ve learned the language and settled in. I’ve always lived in Aichi and Gifu and, when I first came here in 2005, you didn’t see many foreigners outside Nagoya city center. That’s certainly changed so we’re less of a novelty and it means there’s a more diverse range of restaurants, which is always nice! There are still things about Japan that surprise me, or annoy me, but that’s true of Scotland too.

M: I wanted to ask about identity. You write (extremely well) about Scotland and Japan and your experiences and love of both countries. Do you still feel Scottish? Or has your identity changed over the years?

IM: I definitely feel Scottish — it’s a cliche but the further Scots get from home, the more Scottish they become — and there’s always a point in karaoke when I’m drunk enough for “500 Miles,” but identity is an intersection of many things, so being Scottish is just one aspect of my personal identity. Japan is so much more my home now that Scotland is — I went back in March and in many ways it’s become a foreign country to me. Saying that, I can’t see myself ever becoming naturalized and swapping passports — I’m still holding out for a Scottish passport one day.

Just hanging with @Trevornoah on Amazon's memoir best seller list. @BirlinnBooks @PolygonBooks pic.twitter.com/WkpyLaAR9A

— Iain Maloney (@iainmaloney) July 6, 2020

M: The chapter titled “In Rainbows” is really funny. It touches on LGBTQ issues in Japan in a light-hearted manner. Is there much of a LGBTQ scene in the Japanese countryside?

Not really, certainly as far as I’m aware. In that chapter I write about a snack bar in my nearest city run by a gay man — he’s out, but as you’d expect attitudes in the aging countryside are often behind those in the young urban centres. Many people still don’t feel they can come out publicly, or even to their parents. I have a couple of Japanese friends who are out with their close friends, but not more widely. It’s a shame that people still have to hide who they are, but things are slowly changing. I just try to be an ally when I can.

M: You write that “immigrants are immigrants” in the “Refuse/Resist” chapter. Are you a fan of the term “expat” or are expats just immigrants? It seems like being an “expat” is connected with privilege.

IM: I don’t use the term “expat” at all. It’s often used — sometimes unconsciously, sometimes deliberately — to mark a difference between different kinds of immigrants. “Expats are good; immigrants are bad.” It is usually used to mean white immigrants from richer countries — British expats; Chinese immigrants, that kind of thing. I hate that idea. Immigrant isn’t a bad word, it isn’t a negative word, it’s just been hijacked by bigots with an agenda and I refuse to buy into what they’ve done to the language. Expat is a word that has lingered since the days of British colonialism and originally meant someone living in another country temporarily — a merchant sent to India for five years, for example — and who had every intention of going home. I find it funny that people I’ve met who call themselves expats also get angry when they are asked, “When are you going home?” You can’t have it both ways.

M: You write that, “Then, in 2010, Britain voted in a Tory government by accident. In July 2012 the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition changed the immigration rules for non-EU spouses of UK citizens. To qualify for a visa, the UK citizen (me) had to earn more than £18,500 a year in the form of a salary from one source. This job had to be permanent and the employee had to have been in the job for a minimum of a year to qualify. If these criteria were met, the spouse (Minori) would have to pay £3,500 for their visa. If the criteria couldn’t be met, the UK citizen had to have a minimum of £60,000 in savings.”

I think this has had a huge effect on many British nationals in Japan. Could you expand on your feelings about this and the implications of this rule?

IM: The UK immigration policy seems designed to punish people for marrying foreigners, like we’ve somehow betrayed the fatherland. It’s one reason I describe myself as living in exile. I’ve been lucky that my wife and I have good jobs here so the option of living in the UK being taken away from us (most of my income is through freelance sources, so I wouldn’t qualify under the current rules) hasn’t caused many problems beyond anger, but I know for many others it’s had a huge effect. These rules have literally split families with parents forced to live apart from their children, husbands and wives on different continents. The term “Skype family” even entered the dictionary

Purchase “The Only Gaijin in the Village: A Year of Living in Rural Japan” here.

Follow the author on Twitter.

Official Website:

iainmaloney.com