July 15, 2021

Why the World Needs Literature

Conversations with award-winning author Yu Miri and translator Morgan Giles

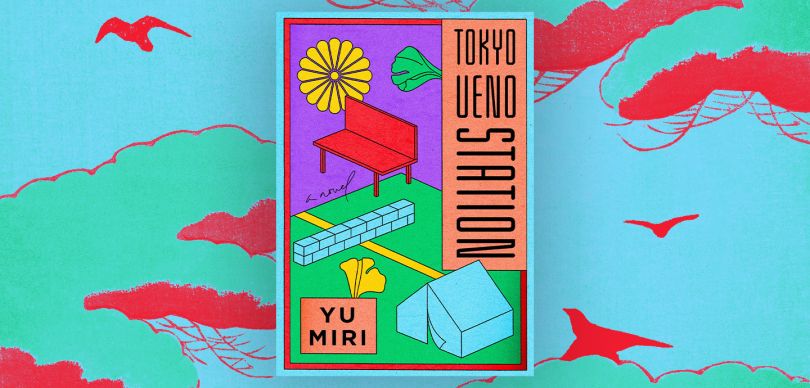

When the National Book Award for Translated Literature was awarded to “Tokyo Ueno Station” by Yu Miri and translated by Morgan Giles in late 2020, it was the second time in three years that a translation from Japanese had won the prestigious award. The impressive achievement signified the unique literary accomplishment of Miri and Giles.

“The book is an observation of Japan […] at multiple thresholds of shifting eras […] told in the bardo of a mourning father and compatriot, reciting his surroundings and circumstances as if a prayer, a mantra,” wrote the judges. “Tokyo Ueno Station” is a bone-crushingly sad observation of contemporary social issues in Japan. Told by a ghost among the homeless of Ueno Park, the narrator reflects on his personal history of tragedy, poverty and fleeting moments of love.

“For many years now, literature in America and Britain has been a too-cool, ironic pose in some senses,” says Giles. “I think ‘Tokyo Ueno Station’ is refreshing because it’s a true expression of actual feelings. You can’t help but to get pulled into feeling something along with the main character.”

Those powerful feelings evoked by the text — and by Miri’s broader catalogue, including the recent notable short story published in Granta Magazine, “North Winds Blow The Leaves From The Trees”— are none other than true, punishing, inescapable loneliness. Miri fearlessly tackles brutal subject material. Homelessness, destitution, suicide, child abuse. But her magnetic, sparse, almost agonized style, aptly captured by Giles in her translations, manifests a deeper and moral purpose of both fiction and translation, and one that makes “Tokyo Ueno Station” all the more worthy of a National Book Award — the power to give a voice to the voiceless.

The homeless people, ignored by their city. The people of Fukushima, ignored by their government. Zainichi Koreans, ignored by society.

“Miri started writing because she didn’t feel that she had a place where she belonged and she wanted to create a place for herself,” says Giles. “Now, her goal has shifted to creating a place in literature for all the people who feel like they don’t belong in this world.”

“North Winds Blow The Leaves From The Trees” is the prototypical Miri story in a nutshell. The story is about a woman displaced from her home with her mother after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, living in temporary housing. Her mother has just died. The narrator flashes back to her old home, now under plans for demolition, her violent father she never knew, and the life of her mother. Told squarely within the frame of the narrator’s consciousness, Miri’s writing is halting, rigid, quiet. The pain of the narrator comes through sharply in the prose:

“After her cremation, I took mum’s remains back to temporary housing. I placed the urn on top of the kotatsu, and without a sigh, I began to deal with her belongings. Ever since the day of the disaster I had walked hand in hand with my mother through the darkness. Now, if I didn’t untangle my hand from hers, I would have nowhere to go but to my death.”

Literature in America and Britain has been a too-cool, ironic pose in some senses. ‘Tokyo Ueno Station’ is refreshing because it’s a true expression of actual feelings.

Like “Tokyo Ueno Station,” “North Winds” is a showcase in radical empathy. Miri creates the voices and evokes the pain of the many people who have suffered immensely from disaster, tragedy and social ills. She gives the reader a chance to identify with those that have suffered, to think about our fellow human beings in a new light.

The narrator completes the painful process of demolishing her old house and buying a new one without the eventual consent of her mother. Standing alone in the house, a painfully real picture of loneliness emerges. Miri writes, “My voice reverberated in this strange house. There was only one mouth in this house that could raise a cry, and that terrified me. I could not speak. I could not talk to myself. My voice would only reach my own ears.”

It’s not all punishingly sad. Moments of beauty, wit and truth shine through. But on the whole, Miri’s writing is relentless in its commitment to tackling human suffering.

In order to write and translate these experiences without necessarily having gone through all of them first-hand, both Miri and Giles turned aggressively to research. Miri had extensive conversations with homeless people in researching “Tokyo Ueno Station,” and she now lives in Minamisoma, a disaster-struck city in Fukushima prefecture. Giles conducted exhaustive research, including conversations with colleagues who have had relevant experiences, and paying them for their time.

“There’s always some element of artifice in translation,” says Giles. “It’s partly why readers distrust translators — because they’re concerned that they’re not getting the authentic experience of the text. For me, the only way I can get past that is to involve myself in the text as deeply as I can. I don’t approach her translations like an academic, because it isn’t academic. It’s about real people and their actual lives.

“The End of August” is the latest of Yu Miri’s works to be translated. A multigenerational, taboo-smashing punch drawing from Miri’s own family history as Zainichi Koreans in Japan, Miri’s masterpiece is set to be one of the most exciting Japanese literature translations of 2022.

The question of authenticity is an important one. How can writers tell and translate stories about marginalized groups without exploitation or appropriation? This question recently emerged in a debate over whether translators of laureate poet Amanda Gorman should be Black. Should translators of Japanese fiction be Japanese? Should translators of Fukushima victims be victims of disaster?

The achievement in storytelling and quality of translation by both Miri and Giles offers a road map not via identity, but experience: that the author and translator need to do the work. The authenticity present in Miri’s writing and Giles’ translations emerge from the difficult work of the writer and translator, work that turns into authentic life experience. These stories are both solutions to how writing can give a voice to those that society has left behind, and a recipe for doing so sensitively.

A translated version of Yu Miri’s next novel “The End of August” is slated for next year. It is the partly-true story of Miri’s grandfather, who was a marathon runner in Korea during the Japanese occupation. According to Giles, this massive novel weaves in a multitude of voices to create a rich portrait of life in Korea under Japanese colonialism.

“She has involved Zainichi characters before, but this time she’s putting it all out there,” says Giles. “The novel is incredibly special, not the least because she mixes Korean and Japanese together in the dialogue and prose, but she deploys so many creative ways of bringing these voices in. I’ve read no other novel like this is any language. It’s like training to run a marathon myself.”

“There’s always some element of artifice in translation,” says Giles. “It’s partly why readers distrust translators — because they’re concerned that they’re not getting the authentic experience of the text. For me, the only way I can get past that is to involve myself in the text as deeply as I can. I don’t approach her translations like an academic, because it isn’t academic. It’s about real people and their actual lives.