Kim Kardashian West recently released a line of compression undies and called it “Kimono Solutionwear.” The name received a torrent of backlash, first from prominent and punctual Twitter users like BBC News editor Yuko Kato and kimono designer Maria Kawara. Kardashian earned her own Twitter hashtag (#KimOhNo) and an online petition. Regardless, she announced that she would not change the name, nor release anything that would dishonor the actual kimono. In addition to appropriating the garment’s name, she applied for eight trademarks for the Kimono line, insisting that a trademark would not “preclude or restrict anyone, in this instance, from making kimonos or using the word kimono in reference to the traditional garment.”

Twitter soon died down and it seemed she escaped all demands to rebrand, into the clear — to the purgatorial place all Kardashian drama seems to go, no longer relevant but always lingering on Buzzfeed and in that smug tone people reserve for the Kardashian-Jenners. However, on July 1, Kyoto mayor Daisaku Kadokawa posted a disapproving letter to Kim on his Facebook page. She promptly posted an apology to Instagram and Twitter, promising to rename.

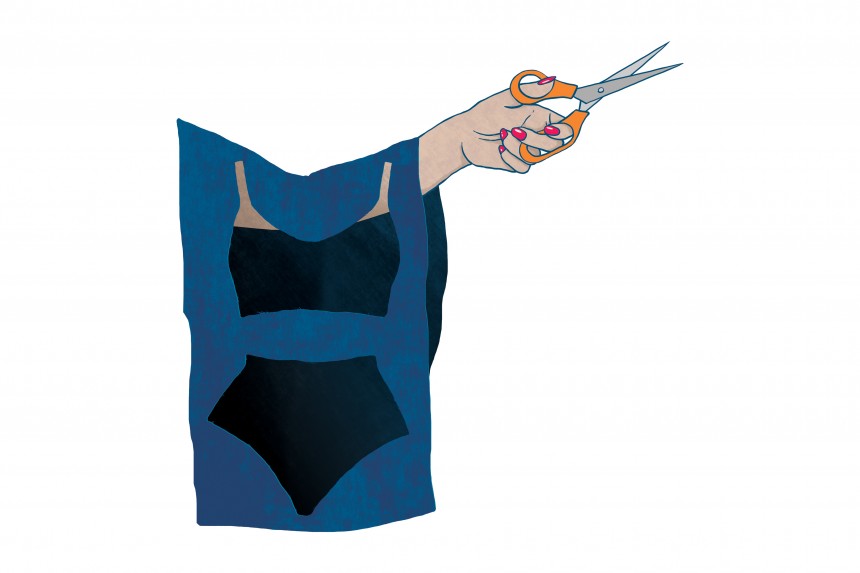

Admittedly, I dismissed the controversy at first. Kim’s slip-up didn’t seem to warrant all the news coverage. Perhaps the Kardashians’ countless other brushes with cultural appropriation had jaded me. But the apology revealed “Kimono” to be more nefarious than I thought. In the Instagram photo, she’s in a dressing room, sitting on a swivel chair, with characteristic perfect hair and perfect face. As usual, her expression doesn’t betray any feelings. The underwear hangs behind her.

She is one of the best marketers in the world, and the caption to this photo only proves her spectacular selling power. She had good intentions, it says. At the core of her brand are “inclusivity and diversity.” Before receiving the mayor’s letter she told The New York Times that the name was “a nod to the beauty and detail that goes into a garment,” but it was clearly more punny in intention, an exotic-sounding clothing item with her name on it. Consider her other brands, KKW Beauty and Kimoji, whose names also keep with the Kardashian marketing credo: Kim’s face, body and name shall pervade every part of the product. This Kim-centrism is applied to every step of every mention of the product, from announcement to apology — hence the Instagram post, in which she places herself at the center of the controversy (“I am always listening, learning and growing …”) rather than at its source. Her initial mistake isn’t the moral of this lesson. Neither is the new title of the underwear. The moral is found in much of the backlash — namely, concerns for the cultural symbol in question.

She mentioned that “varied perspectives” were expressed but failed to mention the criticisms, the mayor’s letter or the namesake garment; she didn’t say the word “kimono” once, even in reference to the lingerie line. Thus, she only repeated her first mistake, which was to ignore the meaning, history, wearers and creators of the actual kimono.

When you use a cultural artifact, a name or design, for commercial purposes without referencing its history or regional significance, you claim it for yourself and diminish its meaning. For example, there was concern that the name “Kimono Solutionwear” erased thousands of years of history, and would change people’s ideas of what a kimono was. Western fashion brands come to mind, with their inclination for Indigenous art. A dress in Isabel Marant’s Spring/Summer 2015 Étoile line borrowed embroidery patterns from the huipil, a traditional blouse of the Mixe people from Oaxaca, Mexico. Marant didn’t get permission from Mixe artisans or seek their collaboration. By claiming the designs without crediting or working with its creators, the huipil was cheapened, its original meaning gone.

By discussing her underwear and the brand name rather than the kimono and her critics’ concerns, Kardashian further neglected the garment’s significance. In cases like this, there’s a tendency to decry the “cultural appropriator” at the cost of ignoring the “appropriated” item, and she only advanced this idea that her doing something controversial and problematic is chief in importance — not the possible cultural erosion, not the traditions at stake.

This is not to say foreigners are barred from wearing kimono. Quite the opposite: the Mixe community invited Isabel Marant to meet their artisans. Likewise, Mayor Kadokawa invited Kardashian in his letter to visit Kyoto to “experience the essence of Kimono Culture.” Yoshifumi Nakazaki, deputy director general of the Japan Kimono League, called the kimono garment, name and history a “common asset.” However, those who borrow a cultural artifact or its name should familiarize themselves with the parent culture and, concerning original artworks like huipil embroidery, give credit where credit is due. And, since appropriation without due credit is hardly preventable, ensuing apologies should at least touch on the meaning of the artifact. It would’ve been nice if Kardashian referred to Kimono Culture or the surrounding history. Perhaps her trademark and her apology aren’t as tangible as a $395 Marant dress, the “appropriation” involved not quite as blatant, but the implications are the same: diluting culture to sell a pretty thing.