October 4, 2022

The Rise of Multicultural Japanese Literature

Real, imagined, or hiding this whole time?

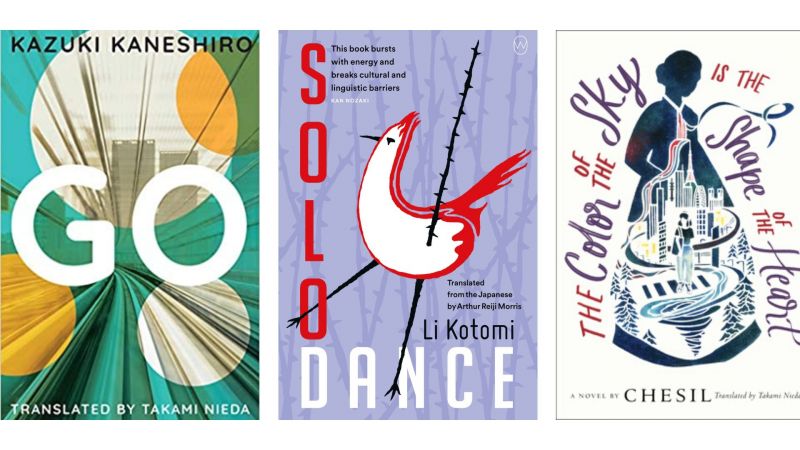

Several notable Japanese books in translation in the last few years have come from non-traditionally “Japanese” perspectives. This year alone, Li Kotomi’s Solo Dance, about a queer Taiwanese woman working in Japan, and Chesil’s The Color of the Sky Is the Shape of the Heart, about a teenage Zainichi Korean who moves to the U.S., arrived in English. Chesil’s novel comes a few years after the English translation of Go, by Kazuki Kaneshiro, another Zainichi author, was released in English translation in 2018.

Meanwhile, in Japan, plenty of other stories have recently achieved impressive heights of critical acclaim and commercial success. Kawagoe Soichi’s Naoki Prize-winning Netsugen (Heat Source, 2019) is an Ainu historical epic; long-famed writer Yuko Tsushima’s posthumous Yamaneko Domu (Wildcat Dome, 2017) is a dizzying mystery centering half-Japanese orphans. Ushio Fukuzawa has written several critically acclaimed novels centering the Zainichi experience, most recently Umi o Daite Tsuki ni Nemuru (Cling to the Sea and Sleep on the Moon, 2018).

Since 2008, two non-Japanese native authors—Yang Yi and Li Kotomi—have won the famed Akutagawa Prize, and others such as Wen Yuju have also been nominated. Is it fair to say that more diverse Japanese literature is on the rise both at home and in translation?

To answer this question, one needs to look at the historical nature of Japanese literature—which, literary translator Lisa Kuroda Hoffman points out, has diverse origins.

“The distinction between who is and isn’t Japanese has not been constant throughout Japanese history,” Hoffman says. “Poets and intellectuals from the Korean kingdoms of Silla and Baekje were instrumental in introducing ‘civilization’ as we know it, and some of the earliest Japanese imperial court collections include poems by Korean poets and ambassadors.”

Later, Hoffman points out, Koreans and Chinese under the Japanese empire were encouraged to produce literature in Japanese, which circulated at home as proof of successful assimilation. Zainichi writing and culture achieved the limelight many times in postwar Japan, including when Lee Hoesung won the Akutagawa Prize in 1972, Lee Yangji in 1988, and during a wave of successful Zainichi cinema in the early 2000s.

Understanding whether or not Japanese literature is changing also requires defining “Japanese literature,” and defining the “Japanese” part of the term is challenging enough. Does writing in other languages by diaspora Japanese qualify? Or writing by non-ethnically Japanese writers living in Japan in Japanese, or other languages?

All of these concepts are evolving, and often for good reason. “Although it is still quite common to fall back into the nihonjin/gaikokujin distinction, a binary which assumes all ‘Japanese people’ are ethnically Japanese, native Japanese speakers… the use of new and more specific terminology such as nihongowasha is promising because it attempts to categorize people by their preferred language,” says Hoffman.

For the purpose of this article, I’ll refer to “Japanese literature” as works written in Japanese and “based”—either because of the location of the author or the author’s ethnicity—in Japan in some way.

In terms of the “literature” part, looking at major awards like Akutagawa and the Naoki Prize is a good start. An examination of Japanese literary history uncovers acclaimed ‘diverse’ authors with regular frequency. At the absolute minimum, Zainichi authors like Gen Getsu and Kim Sok-pom won major literary awards in the 50s, the 60s, the 70s (twice), the 80s (twice), then eight times in the 90s, three times in the 00s, four times in the 2010s, and in 2020; Chinese and Taiwanese-born authors like Chin Shunshin and Akira Higashiyama in the 60s, the 80s, the 90s (twice), the 00s (five times), the 2010s (five times), and 2021 (twice); European and American-born authors like Levy Hideo and David Zoppeti in the 90s (twice), the 00s (twice), and the 2010s (twice); and mixed-race Japanese like Anna Ogino once in the 50s, 60s, 90s, and 00s. It’s worth noting that all of these figures are rough minimums.

The numbers reveal that diverse Japanese authors started to arrive at the top of the literary world in the 90s, and have continued to gain traction since then. But it’s worth noting Zainichi authors in particular have been a core part of high Japanese literature since long before that.

Still, this world of literature is extremely narrow and excludes the vast majority of the books published under my definition of Japanese literature. It’s an impossible task to analyze the entire Japanese publishing market, but editors at several Japanese publishers mentioned to me in passing that they did feel like more diverse stories were becoming a staple of the marketplace, including works centering LGTBQ+ stories.

“I think talking about political matters in literature has been regarded as ‘tacky’ and therefore avoided,” says Saori Kuramoto, a book reviewer at Kyodo News, Bungei, and more. “The tide turned when writers with cross-cultural roots such as Wen Yuju and Li Kotomi began to actively speak out as ‘parties of interest.’ …I believe that Japanese readers have begun to take notice of the importance of each individual making their voice heard. In this process, they began to pay attention to identities that were previously ostracized from the conventional image of ‘Japanese.’” Kuramoto also points out that the rise of Korean literature in the Internet age has also had a major impact on an increasingly open literary atmosphere.

There is no doubt that the foreign market’s increased appetite for diverse stories can and may already be helping to fuel the translation of new kinds of Japanese fiction. Reporting in the U.S. suggests an increased demand for more diverse fiction, and it stands to reason that stories about non-standard Japanese backgrounds will stand to gain in the English-book market as a result.

“As the Anglophone publishing world becomes open to thinking about a more diverse readership (beyond the mythical white, middle-class American reader),” says Hoffman, “these more non-traditional Japanese narratives will I think gain a foothold, and as Japanese readers see these works being translated and celebrated overseas, hopefully, it will spark even more interest and support for these stories in Japan, too.”

The celebration of Japanese authors abroad has some level of sway over the marketing and marketplace for Japanese books in Japan, although authors like Haruki Murakami do remain more popular abroad than at home.

While it’s difficult to say for certain, diversity seems to be on the rise in the world of Japanese books. In fact, it’s translation that still has a long way to go to catch up with the diversity of authors that have been established in Japan for years, decades, and even centuries. The rise of multicultural Japanese literature is all three: real, imagined, and left unnoticed by the English-speaking world this whole time.