August 20, 2024

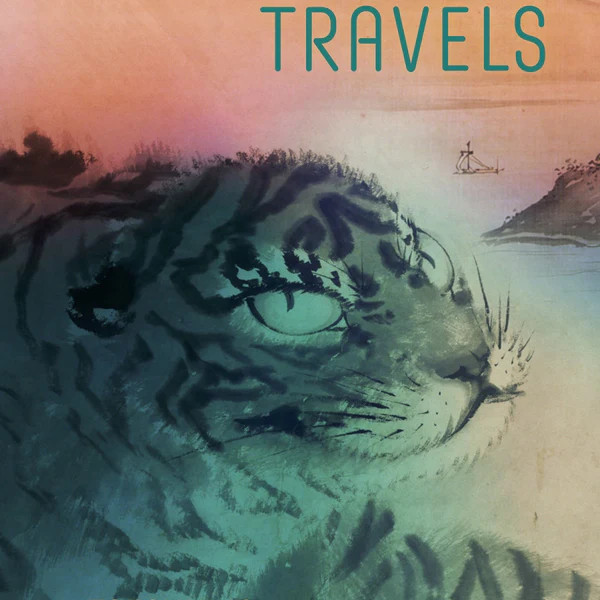

Fresh Ink: A Fantastical Adventure from Medieval Japan–Takaoka’s Travels

Dreams, desires and delusional thoughts on a journey far west

There is no English-language author who could weave an authentic tale about a legendary Japanese prince’s journey to the West. And no, not the European west – the west of Hindustan, or India, the birthplace of Buddhism. No Japanese person ever had reached this place, at least as of the year 865, when the novel “Takaoka’s Travels” takes place. But that is the power of translation. Only through translation would it be possible to embark on a dreamy adventure through spacetime into the Orient at the height of the T’ang Dynasty (618-907 CE).

Written by Tatsuhiko Shibusawa and first published in 1987, and then translated by David Boyd, Takaoka’s Travels celebrated its English-language release in May 2024. It tells the story of Takaoka Shinno, a Japanese prince born at the dawn of the Heian Period (794-1185). At the time, art and court culture flourished in the capital of Kyoto. Takaoka was disgraced from Kyoto after his father conspired against the emperor. He grew up to become a Buddhist monk and later aspired to travel to India. And, although he failed in his goal, he made it as far as Singapore, making him the first Japanese person to have traveled so far west. The first recorded Japanese visit to India wouldn’t happen until the 16th century – 700 years later. So while Takaoka failed in his mission, he still achieved something pretty darn impressive.

A Fantastic Tale

But this novel is anything but an accurate account of Prince Takaoka’s voyage. It’s a series of fantasies, dreams, dreams of fantasies and fantasies of dreams. Shibusawa eschews narrative logic, continuity, and even integrity, creating contradictions, loopholes, and startling visions of the fantastic and profound at every turn. Such rashness and boldness were typical of Shibusawa (b. 1928), who made his name by embracing the outrageous and obscene. He first emerged on the literary scene as a translator of French literature, most notably André Breton and Marquis de Sade. (Actually, he was convicted in Japanese courts for being too obscene in his translation of de Sade’s “Juliette”.) He wrote Takaoka’s Travels much later in life, but the novel’s psychologically-tinged mysticism fits into his long career of essay-writing, which often focused on the demonic and the erotic – two motifs that are ever-present on Takaoka’s journey.

Shibusawa carefully balances two contrasting poles: the travelog of an adventure through medieval Asia, and a barrage of Freudian fantasy dream sequences. On the one hand, each chapter follows a particular segment or incident as Takaoka moves further west and closer to India, grounded in exotic but realistic cross-cultural encounters with history, geography and diverse peoples. In the first chapter, “The Dugong,” that means departing from the thriving port city of Guangzhou and encountering a young stowaway. On the other hand, each chapter involves a concoction of magical realism, dreams and fantasy that defy all logic and explanation–In Chapter One, a series of talking fantastic beasts of past and future lore.

A Freudian Fever Dream of Self-Exploration

The fun of the work comes from this two-sided aspect. Sometimes, I found myself captivated by the ornate kingdoms and curious customs of the various Southeast Asian lands Takaoka visits. At other times, I fell into the prince’s elaborate dreams, a series of absurdities, each trying to outdo the previous. Shibusawa at times intentionally contradicts himself, or even deliberately points out when the events of his tale are impossible or simply don’t make sense.

These postmodern devices can make the story feel dreamy to the point of flimsy at times, they don’t cut back on narrative depth. There is an ugly complex lurking beneath the story. Namely, Takaoka’s relationship as a boy with his father’s consort, the alluring Kusuko, a master of the medical, pharmaceutical and erotic arts. This psychological, Freudian element is at the core of Takaoka’s motivation for his journey and makes it far from a classical Buddhist search for enlightenment. Shibusawa clouds the pursuit of nirvana with subconscious sexual urges, as many of the fantastic happenings are laced with sexuality and eroticism. But Shibusawa does not so much as contrast these two worlds as demonstrate their intricate interconnection. Any epic journey, even one across continents, is also a journey across the crooked contours of one’s own psychology.

The Doings of a Conflicted Character

Accordingly, Takaoka is anything but a typical hero. He is a curious and lively character, with strange urges, who lives on a whim. This boundless curiosity allows him to encounter feathered women and petrified men alike. But he is self-absorbed and fickle. The more profound depths of this work reside in the clouded corners of his consciousness. Shibusawa spotlights uncomfortable links between lust and travel, enlightenment and narcissism. These disturb the traditional narrative of the spiritual quest, the classical journey that leads to self-discovery. They also disrupt any kind of simple Freudian description of the uncanny as coming from aspects of the subconscious. The worlds that Takaoka encounters are all their own, as much as a reader might be tempted to see them as direct reflections of the prince’s repressed sexual urges.

An effective and confident translation by David Boyd captures Shibusawa’s playful tone, with its grand echo of a classical journey laced with postmodern spunk. A great success of the translation is the way it manages to introduce countless unfamiliar places, objects and mythologies to an English reader without overexplaining. (Although admittedly, I found myself sorely wanting a map to reference.)

Traveling as a Confrontation with Yourself

Takaoka’s Travels enables us to step into worlds we could scarcely imagine. Our journey to Hindustan, thus, is much like Prince Takaoka’s – we face one completely unfamiliar sight after another. We are left to either try to dissect and connect new wonders with our own lives, or simply navel-gaze in wonder and ignorance.

A viral New Yorker article, “The Case Against Travel” recently argued against travel, saying that travel is often a simple excuse to tell ourselves that we’ve changed, when we really haven’t. Shibusawa, in one sense, proves this pessimistic thesis—does Takaoka really grow on his journey at all, despite it being the most epic in Japanese history? But at the same time, Shibusawa shows us the limitless and even magical possibilities of travel. A reader can see that Takaoka, not his travels, are the only thing to blame for him being stuck in himself and his past. We can therefore see that wonder truly just awaits on the high seas—albeit wonder that can only come partially from dreams that are all our own.